It’s the battle of the Barbers!

Early last week, I posted about how I had inadvertently scheduled two concerts on the same day, both of them featuring the Samuel Barber Violin Concerto.

How did it happen? I impulsively acquired a seat to Friday afternoon’s Philadelphia Orchestra concert, practically as an afterthought, to fill-out the quota for a package deal for deeply-discounted tickets. What I’d failed to take into account was that I was already set to hear the concerto in Princeton on Friday evening, on a program presented by the New Jersey Symphony!

An embarrassment of riches, then, and a rare opportunity to juxtapose two interpretations of the same work, which turned out to be quite different from one another.

Classical music enthusiasts tend to toss around a lot of comparatives, and most of them incline toward the hyperbolic: This is the best recording. That performance was terrible! He was the greatest violinist of all time, and so forth. But really, is life always screwed to such a fever pitch? Is there no room for nuance?

I’ll offer my personal assessments of this weekend’s performances at the end of this post – and I can’t promise that they will be without overzealous comparatives – but first, a few words on my history with this particular concerto:

The first time I encountered the work was on a concert of the Philadelphia Orchestra, back in 1986. Elmar Oliveira was the soloist, and – can you imagine? – the concerto was on the same program as Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 6! Riccardo Muti, then the orchestra’s music director, conducted. What an evening! I hasten to add that Prokofiev was probably my favorite composer at the time, and I was devouring all of his music that I could.

Of course, I was still learning the repertoire, and as a young person, the frontier seemed wide-open. Whenever I encountered something I liked, I raced to the record store as soon as I had the funds to acquire it. I very quickly figured out that the most efficient way for me to accomplish this was to actually get a job as a record clerk – which I did, at a Sam Goody at 11th and Chestnut Streets, which at the time had the most extensive classical music section in the city. (This was before the arrival of Tower Records.)

Can you believe we had three people working the classical department? That’s what record stores were like in those days, when the technological development of the compact disc injected new life into the industry, with collectors eager to upgrade their libraries and push the limits of their audio equipment. It was there that I acquired Neeme Järvi’s Prokofiev cycle. Essentially, I wound up turning over most of my paycheck for the blister-packaged merchandise I had squirreled away in a cardboard cubby in the basement. I was still quite green, frankly, but I did have a greater-than-average knowledge of classical music, and as they say, in the kingdom of the blind, the man with one eye is king.

This may seem like another one of my flighty digressions, but I offer it as backdrop to the acquisition of my first recording of the Barber concerto. I was still buying used LPs, and some of the new soundtrack albums were still being released exclusively on vinyl, but by this point CDs had become an obsession. Isaac Stern’s classic recording of the Barber, with Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, had yet to be reissued, and there really wasn’t very much competition on compact disc. The recording we had in stock, on the ProArte label, featured Joseph Silverstein as the soloist. He also conducted the rest of the selections, with the Utah Symphony, including Barber’s “The School for Scandal Overture” and the Second Essay for Orchestra. It actually turned out to be a very satisfying disc.

Oliveira finally recorded the concerto himself, with Leonard Slatkin and the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, his performance released on EMI in 1987. On the same disc was Howard Hanson’s “Romantic” Symphony. I remember my heart was beating so fast when I discovered this at the local mall. Now there are so many recordings of each.

For a time in the early ‘90s, I used a lugubrious passage from the slow movement of the concerto as a music bed on my answering machine. I was in my early 20s, licking my wounds from having been dumped by my college girlfriend. We were together for five years, basically, and it was not a clean break. Also, I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. I’d taken a year to pound out some stories and send them to some magazines, while working at a Holiday Inn, delivering pizzas, etc.

Now I was caught in a series of dead-end retail jobs, mostly bookstores, with a bunch of other drifters, and it took me a few years to finally figure out that I could start my own. Of course, as soon as I moved on it and signed a lease on a store front, I was called to come in for the interview that landed me my first paid job as a classical music radio host. A Ross divided against himself cannot stand! Nevertheless, I continued the balancing act for the next 13 years, sleeping very little, I might add. Then I packed in the books (not that I’ve unloaded them all) and kept on with the radio.

But at the time I mention, in the early ‘90s, I was still wallowing in an impecunious quagmire, on my feet all day, working myself into exhaustion at a Barnes & Noble superstore, then coming home and blacking out on a fold-out sleeper sofa for an hour or so, before sitting down to a bowl of potato gruel and an evening of Wagner or Mahler on the old hi-fi.

It won’t surprise you to learn, I was often late on the rent. This is always stressful, but especially so, when your landlord lives in the same building. In this case, I was on the first floor, in an efficiency in the back of the building, with very little sunlight, but a tiny yard where I could enjoy my coffee in the morning and air out my clothes after a night downing Yuengling at a local dive bar.

Awkwardly, the fire escape was right behind the sofa bed, so that every morning I would see my landlord walk down the steps with his bicycle, before pedaling off to his university job. As he was a professor of English literature, I had hoped that maybe he could pass along some leads to some employment opportunities (this was in the days before the internet) – I was, after all, an English major – but he never knew of anything. Anyway, sometimes he would phone my machine. Once, he left a message, probably hoping for the rent, in which he remarked, “Samuel Barber is not half so ominous as you are.”

At work, I was always ordering books for myself, taking advantage of the employee discount. So another time, I was standing right next to one of my coworkers, whose task it was to call customers to notify them that their orders had come in. I wasn’t really paying attention, but after she hung up the phone, she muttered, “That guy’s machine sounds like a funeral parlor.” I took a look at the slip and busted out laughing. Of course that guy was me, my funereal manner enhanced by the Barber Violin Concerto.

Barber’s concerto, composed in 1939, is unapologetically lyrical, with long-limbed melodies and, in its first two movements, a yearning, even elegiac, quality. The final movement is an about-face, a grotesque moto perpetuo, during which the soloist is let off the leash for a thrilling romp around the park.

The first public performance was given by violinist Albert Spalding, with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy at the Academy of Music at Broad and Locust Streets in 1941. I wonder if Barber, who died in 1981, could ever have anticipated just how much this concerto would take off. I doubt if there’s a major violinist in the world today who doesn’t have it in their repertoire.

But times were different in the 1940s. WPA-style composers were writing big, populist ballets and symphonies to boost morale during World War II, but all the while avant-gardists, many of whom embraced Arnold Schoenberg’s rejection of tonality, were engaged in subverting what they regarded as dangerously subjective, overly emotional (i.e. irrational) tendencies that had propelled civilization into two cataclysmic wars. In their place, they advocated a coolly rational, more objective music. Big, Romantic gestures were eyed with suspicion, if not disdain, and academics and public (the latter always appreciative of a good tune) parted ways.

Like Rachmaninoff, Barber was viewed as something of an anachronism. Unlike Rachmaninoff, he didn’t make the piano the center of his output. Nor did he possess the virtuosic technique as a performer to whip audiences into a frenzy. Anyway, Barber, though clearly capable of expressing emotion (as in his famous “Adagio for Strings”), preferred to do so with dignity and restraint. His preferred idiom was post-Brahmsian. There are flashes of anguish, but he never allows himself to wallow or teeter over into hysteria.

Perhaps this explains Augustin Hadelich’s interpretative decisions on Friday afternoon in Philadelphia. His take on the Violin Concerto was restrained to a fault – intimate, surely, but practically interior, for most of it nearly to the point to disengagement. There is something to be said for subtlety, and Barber himself would have been horrified ever to be caught blubbering. But there is a difference between drawing the listener in and leaving him or her out in the cold. Others may have reacted differently – there were cheers and the requisite standing ovation – but I didn’t find it particularly involving. As with “Hamnet,” I never would have survived without a cup of coffee. In the last movement, Hadelich proved – as if he needed to – that he was up to the work’s technical challenges, He’s a super violinist, who played a memorable Sibelius concerto when I last saw him in Philadelphia a few seasons ago – but I’m afraid it was too little, too late, and I came away feeling as if the whole thing had been underpowered.

I wonder too if trying too much to sculpt the music robbed it of some of its allure. On the second half of the concert, I felt Mahler’s Symphony No. 4, though one of his more intimate works, was also marred, a few passages aside, for the same reason – by babying it too much. Ironically, the work is infused with suggestions of childhood – quotations of folk song from the collection “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” and the final text relating a child’s vision of Heaven. (Once she settled in, soprano Joélle Harvey was radiant.) But there are also insinuating, sinister forces at play – dances of death, suggestions of funeral marches, and so forth. Except for those moments when, for instance, timpanist Don Liuzzi was allowed to rip, the performance turned out to be no more than up to the Philadelphia Orchestra’s usual fine standard, but in no way exceeding it.

It pains me to say so, since I am an admirer of the conductor, Dalia Stasevska. A few years ago, she conducted a Sibelius 5th Symphony that so far exceeded Esa-Pekka Salonen’s rendition when I heard him with the orchestra the following season, it wasn’t even in the same universe. Though Stasevska was born in Ukraine, both conductors are Finnish-bred. However, Stasevska does Salonen one better by being married to Sibelius’ great-grandson!

The whole experience was eclipsed by what I heard in Princeton on Friday evening, when Randall Goosby joined the New Jersey Symphony for a richly-satisfying performance of the Barber. I wonder if the individual venues might also have influenced my judgment. Hadelich played at somewhat of a remove in the cavernous Marian Anderson Hall at Philadelphia’s cathedral-like Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. Goosby played in the much more intimate Richardson Auditorium at Princeton University, where the performers are practically in your lap. So Goosby’s instrument could be heard even in the work’s orchestral climaxes. But overall, my impression was that Hadelich was living in his head, while Goosby was letting us into his heart.

Of course, the conductor was the New Jersey Symphony’s Xian Zhang, whose podium manner makes Leonard Bernstein seem positively restrained by comparison. Zhang works hard, sometimes distractingly so, as she attempts to convey a sense of energy to her players, and I have to admit, it sometimes lends to the excitement of the performance. At others, it can be so over the top, you can’t help but smile. But is that such a bad thing? Especially when the second half of the program was Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 2, once commonly nicknamed in English-speaking countries the “Little Russian,” until world events precipitated a shift toward identifying it as the “Ukrainian.” Tchaikovsky lived and composed in Ukraine for part of the year, and the work is infused with Ukrainian folk song. The music is infectious, totally sidestepping the pathos of the later, more commonly-performed symphonies, with a march in place of the standard slow movement. The piece is downright balletic at times, and the climax is so manic that I couldn’t help but burst into laughter a few bars before the end.

This is the work George Plimpton wrote about after touring with the New York Philharmonic as a celebrity guest percussionist. Of course, Plimpton wasn’t a musician. That was his whole schtick – join the professionals, whether they be football players, boxers, or musicians, and then write about the experience. Plimpton had one job. He had to strike the gong in an exposed, pregnant moment, before a final mad crescendo to the double-bar line. He tells us that in his adrenaline rush, he smacked the thing so hard, he saw Bernstein’s eyes widen, and the shock wave travel out across the musicians into the audience to the back of the hall, and then the orchestra had to wait for the sound to decay so that they could start to play again.

Friday night’s gong-strike was not quite that egregious, but the performance itself was thrilling in the extreme, and altogether much more satisfying than anything I heard from the orchestra’s starrier rivals in Philadelphia that afternoon. I mean, come on. The concert opened with “Finlandia,” for crying out loud. If that doesn’t prime an audience, I don’t know what will.

So in the battle of the Barbers, the championship belt goes to Goosby. I still have faith in Hadelich, a marvelous violinist. Both artists are very much in their prime, and I look forward to, if not a rematch, then many happy musical experiences with them in the years ahead.

——–

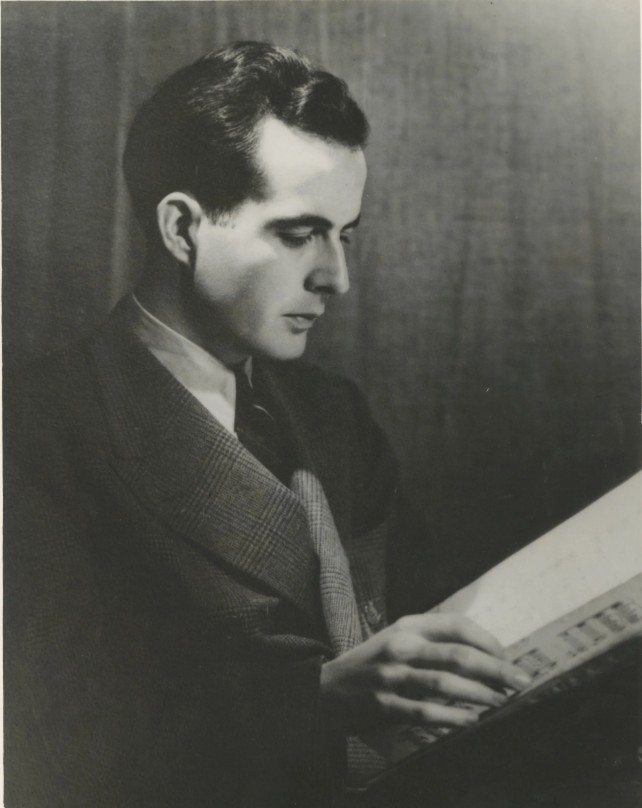

PHOTO: Samuel Barber in 1941

Tag: Augustin Hadelich

-

Brahms’ Intense Piano Quintet at Marlboro Music

Don’t expect anything too drowsy on this week’s “Music from Marlboro,” when the focus will be on Johannes Brahms’ unusually intense Piano Quintet in F minor.

This is not music of wistful reflection. The quintet is often tempestuous and even tragic, fueled by all the passion and earnestness of an excitable young man. Brahms began his quintet in 1862. He was 29 years-old.

That’s not to say the composer ever teeters over into sentiment or excess of a kind common to his fin-de-siècle successors. Even in his 20s, Brahms was too much himself ever to allow that to happen.

Instead he takes the prototype of the piano quintet – established by his friend and mentor, Robert Schumann – and fashions it into something unsettled and at times downright sublime. We are in the presence of something great, but also perhaps a little terrifying.

This masterpiece of Brahms’ early maturity began life as a string quintet, written under the spell of Schubert’s famous Quintet in C. Brahms showed the work in this form to Clara Schumann and his friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim. Both were full of praise, at least at first, but gradually their compliments became outpaced by their suggestions. Joachim, in particular, admired the work’s power, but confessed he found little in it to charm.

Undaunted, Brahms took the piece and arranged it for two pianos in 1863-64, consigning the original version, for strings alone, to flames of woe. This two-piano reworking was more politely than enthusiastically received, and Clara, thinking it sounded more like a transcription now than an original composition, begged him to recast it once more.

The third time proved to be a charm. The resulting quintet, which achieved its final state in the summer of 1864, was met with resounding acclaim. At last, the piece had arrived at a perfect marriage of expression and form.

While Brahms retains the classical poise for which is so well known, he stiffens the sinews and conjures the blood, so to speak. In fact, there are times when he ratchets up the tension so effectively it seems the music might just fly off the rails.

We’ll hear an exciting performance from the 2007 Marlboro Music Festival, featuring pianist Richard Goode, violinists Augustin Hadelich and Benjamin Beilman, violist Samuel Rhodes, and cellist Amir Eldan.

Proceed at your own risk. Safety gear will not be provided, on this week’s “Music from Marlboro,” this Wednesday evening at 6:00 EDT, on WWFM – The Classical Network and wwfm.org.

Marlboro School of Music and Festival: Official Page

Tag Cloud

Aaron Copland (92) Beethoven (94) Composer (114) Conductor (84) Film Music (106) Film Score (143) Film Scores (255) Halloween (94) John Williams (179) KWAX (227) Leonard Bernstein (98) Marlboro Music Festival (125) Movie Music (121) Mozart (84) Opera (194) Picture Perfect (174) Princeton Symphony Orchestra (102) Radio (86) Ross Amico (244) Roy's Tie-Dye Sci-Fi Corner (290) The Classical Network (101) The Lost Chord (268) Vaughan Williams (97) WPRB (396) WWFM (881)