Beethoven (1770-1827) and Jane Austen (1775-1817) share a birthday!

Although the two were contemporaries, they most certainly never met, although Jane’s family kept music books. 18 collections survive – 600 hundred pieces of sheet music – two of the volumes consisting of music copied out in Jane’s hand.

Beethoven doesn’t appear to have been a great favorite. Rather, the Austens gravitated more toward Clementi, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Pleyel, and Thomas Arne (Jane painstakingly transcribed the overture to “Artexerxes”). Allegedly, in her novels, Austen mentions only one composer by name: Johann Baptist Cramer. I haven’t read enough of her books (only two, but working on a third), or kept notes, to be sure. But there are allusions to others.

The Austen family music books may be perused online, thanks to the University of Southampton. You’ll find access at the bottom of the page at the link:

https://www.southampton.ac.uk/news/2015/12/jane-austen-music-books.page

Gillian Dooley, who catalogued the contents, has written her own book, “She Played and Sang: Jane Austen and Music” (Manchester University Press, 2024), based on her research.

https://janeaustensworld.com/tag/austen-music-manuscripts/

Of perhaps related interest, Sony Classical recently released an album by Jeneba Kanneh-Mason, “Jane Austen’s Piano,” a recital of works Jane might have known, including music by Handel, Haydn, Kiallmark, and Cramer, as well as a transcription of some of Dario Marianelli’s music for the 2005 film adaptation, “Pride & Prejudice.”

https://www.kannehmasons.com/2025/10/03/jeneba-kanneh-masons-new-ep-jane-austen-piano-coming-december-2025-on-sony-classical/

Jane attended recitals in salon settings and opera performances at Covent Garden when visiting her brother in London. She herself played the piano for pleasure.

Happy 250th birthday, Jane Austen, and happy 255, Beethoven!

Tag: Beethoven

-

A Lot of Candles for Beethoven and Jane Austen

-

Beethoven & Beyond Sonatina Delights on KWAX

Think a sonatina for mandolin and piano is a bit far-fetched? Tune in to hear what Beethoven made of it.

This morning on “Sweetness and Light,” the unifying theme is sonatinas, or “little” sonatas.

Florent Schmitt’s “Sonatine en Trio” is a happy discovery indeed. There’s a certain neoclassic quality to the music, which we’ll hear in a version for flute, cello and piano, by a French composer whose orchestral works can be quite opulent. The title itself seems to harken back to an earlier time. In fact, the keyboard part was originally conceived for harpsichord. It’s cheering music, and I think you’ll agree, a great start to the day!

Carlos Guastavino is largely remembered for his songs. He wrote his Sonatina while visiting Manuel de Falla, who spent his final years in self-imposed exile in Cordoba, Argentina, following the Spanish Civil War. We’ll hear it performed by Gila Goldstein from a Centaur Records release, “Latin American Piano Gems,” a transporting collection of works by Ernesto Lecuona, Astor Piazzolla, Manuel Ponce, and Heitor Villa-Lobos.

We’ll also hear Philadelphia composer Romeo Cascarino’s Bassoon Sonata, written after World War II for his Army buddy Sol Schoenbach, principal bassoonist of the Philadelphia Orchestra. “Sonatina” may not be in the title, but the character is light, and the sonata is only seven minutes long!

The program will also include delights by Federico Moreno Torroba, Eugène Bozza, and Erik Satie.

A cup of coffee, a scone, and a soundtrack of sonatinas. Give thanks for life’s “Small Pleasures” on “Sweetness and Light,” this Saturday morning at 11:00 EDT/8:00 PDT, exclusively on KWAX, the radio station of the University of Oregon!

Stream it wherever you are at the link:

-

Last Rose of Summer: 13 Musical Treats

It’s the last day of summer. Take some time to smell the roses. Autumn begins in the Northern Hemisphere tomorrow at 2:19 p.m. EDT.

Thomas Moore’s poem, “The Last Rose of Summer,” was written in 1805. It was set to a traditional Irish tune, “Aisling an Óigfhear,” or “The Young Man’s Dream,” with words and music published together in 1813. The song proved to be a heady inspiration for dozens of composers. It’s interesting to reflect that for Beethoven and his brethren in the early 19th century, this would have been considered a contemporary hit.

According to my internet searches, a gift of 13 roses signifies that we’ll be friends forever. How could I pass that up? In the interest of securing you all as BFFs, here are 13 treatments of “The Last Rose of Summer.”

Sung by Amelita Galli-Curci in 1921

Beethoven, “6 National Airs with Variations,” Op. 105, No. 4 “The Last Rose of Summer”

Ferdinand Ries, Sextet “The Last Rose of Summer” (the tune appears at 11:45)

Carl Czerny, “Variations on ‘The Last Rose of Summer’”

Felix Mendelssohn, “Fantasy on ‘The Last Rose of Summer’”

Sigismond Thalberg, “The Last Rose of Summer”

Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst, “Variations on ‘The Last Rose of Summer’”

Félix Godefroid

Joachim Raff

Max Reger

Paul Hindemith, “On Hearing ‘The Last Rose of Summer’”

Benjamin Britten

Friedrich von Flotow, from his opera “Martha”

IMAGE: “Soul of the Rose,” by John William Waterhouse (1908)

-

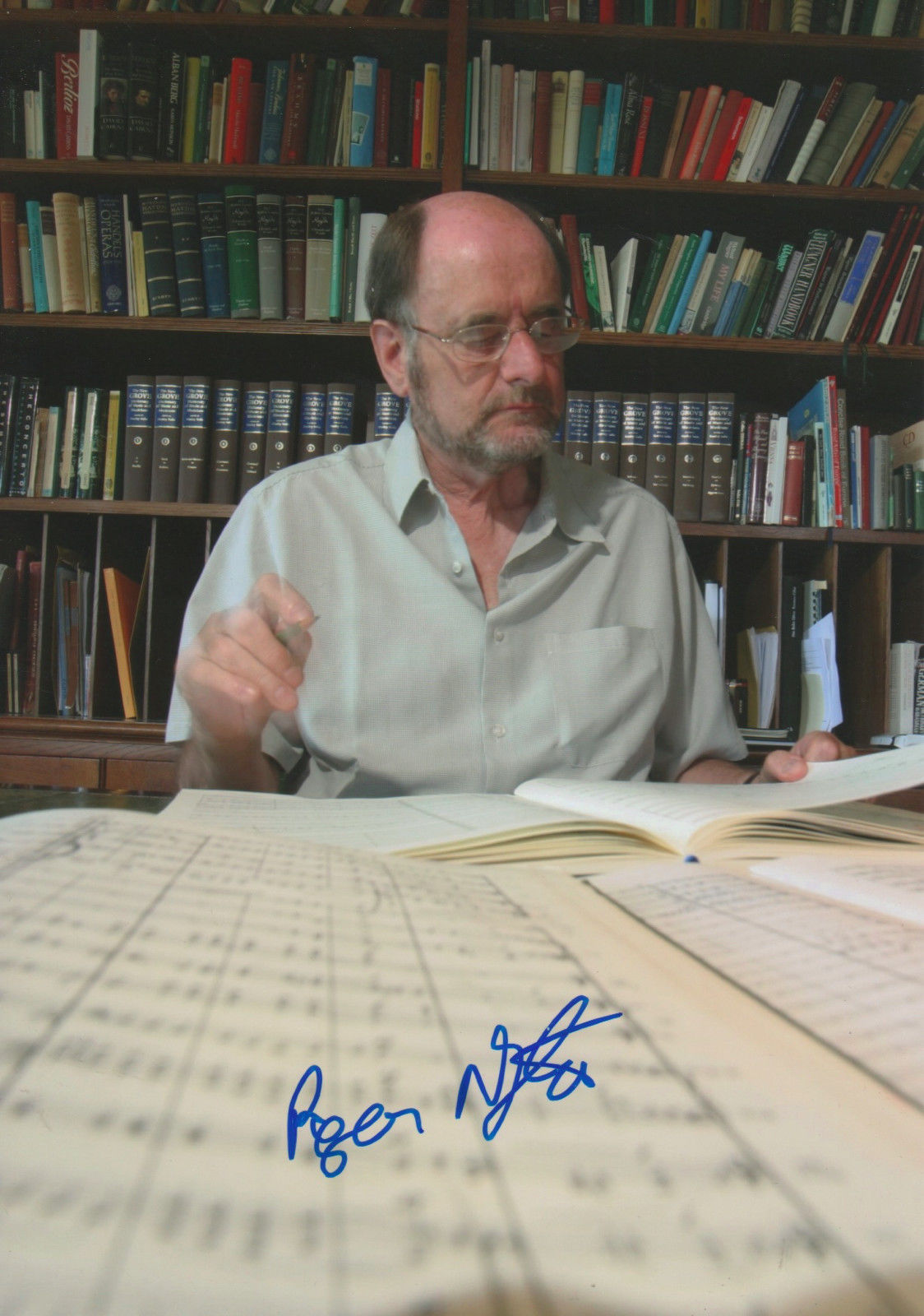

Remembering Roger Norrington

As the interest in period instrument recordings was just beginning to crest in the 1980s, I remember being put off by what I perceived as a kind of “metallic” sound – something of a paradox, since historic instruments flaunted gut strings, made from organic matter (sheep or cattle intestines). Yet the sound impressed me as alien. Clinical. Inhuman. There was just something about many of those CD recordings of Baroque and Classical music of the time that for me lacked warmth. They left me cold.

Roger Norrington was one of the influences that helped expand my consciousness, so that gradually I realized that sometimes the fault, dear Brutus, is not in a performance, but in ourselves. Or to borrow a somewhat folksier insight from George Ives, Charles Ives’ bandmaster father, sometimes our ears can use a good stretching. It’s healthy for music, and healthy for ourselves.

Norrington allowed me to perceive the advantage of regarding the classics from different perspectives, with, of all things, one of his Robert Schumann recordings for EMI. (He later rerecorded the symphonies for Hänssler Classic.) Schumann, a Romantic composer if ever there was one, is quite beyond the jurisdiction of “early music,” or so one would suppose. But that doesn’t mean performance of his works cannot benefit from a contextual lesson from history, or at any rate historical theory. In Schumann, Norrington’s brisk tempi and understatement struck me as novel in music that often benefits from the opposite approach. I hasten to add that this is NOT Schumann for every day, but it is interesting.

Norrington applied his lexicon of “period” practices, compiled through his experiments with Baroque and Classical music, to the works of later masters, viewing their scores not retrospectively, as most conductors were in the habit of doing, but rather chronologically, as extensions of what had come before.

That’s not to say a Norrington performance, regardless of how it was sold, was not, in its way, any less subjective than that of any other conductor. Norrington was frequently pelted with accusations of misguided dogma, but he would have been the first to admit that, at the end of the day, bringing a piece of music to life requires making interpretive choices.

It was Norrington’s Beethoven that really seemed to tickle people’s ears. His performances were characterized by sparse vibrato, fleet tempi, strange sonorities, and shifting seating charts. Controversially, he adhered “strictly” to Beethoven’s metronome markings (though not always). Most conductors have deemed these to be far too fast to properly allow what Beethoven presumably was trying to express in his music.

Norrington was already in his 50s by the time he was propelled to international fame with the launch of his first, ear-catching Beethoven cycle. In retrospect, was it really the lessons of history that made listeners sit up and take notice, or was it the novelty of an interpreter going all in with something new? Does it matter? When packaged as “the one, true way,” I suppose it does. But when viewed as ANOTHER way, well, why not? How is Norrington any different, in his fashion, than Celibidache? Aside from the philosophical underpinnings, I mean?

There’s a lot of guess-work involved in “historically-informed performance.” To a large extent, we don’t know what the music sounded like before the invention of recordings. But the more reputable of its practitioners used sound scholarship to back-up their artistic decisions. Norrington came under fire in some circles for just sort of making things up. It could be especially awkward when ignoring testimonial evidence of conductors who lived from the time of Brahms and Mahler into the stereo era (Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer, Pierre Monteux), all of whom actually knew how this stuff was performed back in the day.

But hey, if it doesn’t distort the composer’s intentions too badly and allows us to hear the music with fresh ears, why not? Norrington was merely the other side of the coin from the Romantic indulgence we experienced with some conductors earlier in the century.

In the end, he might not have expressed it as such, but he could be as much a sensualist as anyone else. Norrington was not some self-abnegating high priest of classical music. Just the opposite. For him, music was not to be approached as a holy relic, but rather as a vehicle for having fun. He promoted a relaxed atmosphere in his concerts, encouraging applause between movements, if the audience was so moved, citing the fact that concerts in the 18th century would have been far from the staid affairs they later became.

His survey of Beethoven piano concertos for EMI, with Melvyn Tan the soloist, performing on a replica of a period keyboard instrument, was another ear-opener. Again, the tinkly, underpowered nature of the fortepiano triggered plenty of aversion at first, but I’ll be damned if it didn’t present the “Choral Fantasy” in a whole new, convincing way.

His second cycle of Beethoven symphonies (for Hänssler), in some respects improves on the first. By then he had moved on from the London Classical Players, the period instrument ensemble he founded in 1978, which often struggled mightily with its anemic, historically-informed instruments, to the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, a modern band, well-versed in the repertoire. When Norrington formed lasting relationships with “modern” groups, such as Stuttgart, the Zurich Chamber Orchestra, or the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, the weird sonorities (mercurial, undernourished strings and unruly brass) were exchanged for a more moderate, middle ground.

Gradually, cumulatively, the world’s major orchestras all came around to the idea that maybe not all music from all periods should be played using the same techniques. Thanks to the efforts of Norrington and his peers (Christopher Hogwood, Trevor Pinnock, John Eliot Gardiner), early music revisionism became normalized, so that now it is rare to hear truly “big band” Mozart and Haydn, for instance, and certainly not Bach. Is the medium subservient to the message? There are plenty of recordings of “old school” Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven to suggest that there are things to relish in either camp.

Norrington, the most hubristic of the period performance practitioners, perhaps overplayed his hand, as he continued to push into the later Romantic era to tackle symphonies by Bruckner and Mahler. Experimentation admits the possibility of disaster. On the other hand, though I was as skeptical as the next guy when he entered the modern era, he managed a satisfying recording of Gustav Holst’s “The Planets,” of all things. (His Elgar was not so fortunate.)

He was also a surprisingly effective advocate of contemporary music. He conducted over 50 first performances and won a Grammy in 2001 for his recording of Nicholas Maw’s Violin Concerto, with Joshua Bell the soloist.

Norrington was no slouch. He studied conducting with Sir Adrian Boult at the Royal Academy of Music, but also composition and music history. He was a violinist and a professional singer, and he played percussion in the conservatory orchestra. Based on his success, he also had a genius for self-promotion and showmanship.

Around his 60th birthday, he experienced some major health scares, when he was diagnosed with melanoma and a brain tumor. At a point, he was given only months to live. Miraculously, he beat it. The illness may have taken the edge off his earlier dynamism, but he retained his mental vigor and sense of joy through his retirement in 2021.

Norrington was knighted for his services to music in 1997. He died on Friday at the age of 91.

R.I.P. Sir Roger.

Norrington introduces and conducts Beethoven’s 8th

Beethoven insights, courtesy of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment

Worthwhile interview with Bruce Duffie

-

Musical Roads Beethoven’s Rumble Strip Craze

The Beethoven rumble strip in the United Arab Emirates has been getting some press recently.

You know what a rumble strip is, right? They’re those irregularities in the pavement installed to jolt you awake when you’re about to drift off the road, or to warn you to slow down when you’re entering a hairpin turn. I suppose it was only a matter of time before someone would figure out that different rhythms and pitches could be produced by varying the spacing of the strips. When driven over at a certain speed recognizable melodies emerge.

Fujairah has decided to emulate Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.”

I don’t know how many of these “musical roads” there are in the world, but the number must currently be pushing 50. (The most recent tabulation I could find was 46 in 2022.)

The first known musical road was created in Denmark in 1995. Argentina, Belarus, China, Hungary, Indonesia, Iran, Russia, San Marino, South Korea, and Taiwan followed. Japan, the musical road champ, has at least 30. The U.S. has at least three. France and the Netherlands had some for a while, but they were paved over.

It’s true, musical roads might be considered a nuisance by some, especially those living nearby, who have to contend not only with the incessant repetition of “Ode to Joy,” for instance, but also increased volume of traffic due to curiosity seekers.

Often the melodies can be made out only when the strips are encountered at a correct, consistent speed. In at least one instance, in California, a strip was paved over after residents complained and then reconstructed elsewhere. Unfortunately, the construction workers confused the measurements, so what you get is a badly out of tune “William Tell Overture.”

One post beneath the video suggests that the tune would sound correct if you hit it at 100 m.p.h. I’m not condoning it; just saying.

Hi ho, Silver! Away!

FUN FACT, though hardly surprising: It was New Jersey that installed the earliest-known rumble strips, on the Garden State Parkway, in 1952.

ADDENDUM: Okay, so it looks like Little Alex and his droogs decided to go back and hit the “William Tell” strip at 100 m.p.h. Still pretty wonky, but worth it for the laugh.

Tag Cloud

Aaron Copland (92) Beethoven (94) Composer (114) Conductor (84) Film Music (106) Film Score (143) Film Scores (255) Halloween (94) John Williams (179) KWAX (227) Leonard Bernstein (98) Marlboro Music Festival (125) Movie Music (121) Mozart (84) Opera (194) Picture Perfect (174) Princeton Symphony Orchestra (102) Radio (86) Ross Amico (244) Roy's Tie-Dye Sci-Fi Corner (290) The Classical Network (101) The Lost Chord (268) Vaughan Williams (97) WPRB (396) WWFM (881)