Only the other day, I was reading about Eleonore Prochaska, a German soldier who fought in the Prussian army against Napoleon during the War of the Sixth Coalition. Prochaska was able to enlist in 1813 by disguising herself as a man, serving first as drummer, but soon entering the infantry. Her true identity was discovered only after she was severely injured at the Battle of Göhrde. She would succumb to her wounds three weeks later.

Prochaska was actually one of a number of women who served in actual battle during the Napoleonic Wars. Rather puts our Molly Pitcher in the shade.

Prochaska’s memory would be celebrated in music in literature. Somehow I never knew that Johann Friedrich Duncker’s drama, “Leonore Prohaska,” for which Ludwig van Beethoven composed incidental music in 1815, was inspired by a real person. I’ve always seen her described as something of an idealized warrior-maiden, a kind of Joan of Arc, who disguises herself as a man in order to fight in an unspecified war of liberation. The fact that Leonore is the also the name of the heroine of Beethoven’s only opera, “Fidelio,” and that in the opera the character also disguises herself as a man – to fight for liberation – probably had a lot to do with it.

“Fidelio” was given its premiere, in its original version, in 1805, but the final revision was performed only in 1814, the year after Prochaska’s death. Certainly, Beethoven’s conception of Leonore predated the actions of the historical Eleonore. In fact, from the start, the composer’s preferred title had been “Leonore, or The Triumph of Married Love” – the title of Jean-Nicolas Bouilly’s play, on which the libretto was based. This was changed only at the insistence of the theater to avoid confusion with at least two rival operas that had drawn from the same source material. Though Beethoven’s work had nothing at all to do with Prochaska, I think it’s an interesting coincidence.

In the end, Duncker’s play was cancelled, and Beethoven’s incidental music was never performed in the context for which it was intended. It wasn’t even published until 1888, 62 years after the composer’s death. Beethoven’s efforts were not for nothing, however, as Duncker, who served as cabinet secretary to Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia, was able to persuade his Royal Highness to underwrite the “Missa solemnis.”

This is a roundabout preamble to my announcement that this week on “The Lost Chord,” we’ll honor Beethoven, on his presumed birthday, with an hour of his incidental music for the theater, including a funeral march from “Leonore Prohaska,” which he arranged from the slow movement of his Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-flat Major.

In 1811, Beethoven was approached to write music for two Hungarian-themed plays by August von Kotzebue. “The Ruins of Athens” and “King Stephen” were scheduled to celebrate the opening of a magnificent new theater in the city of Pest (now the eastern part of unified Budapest). Of the two, “King Stephen” is the less well-known. Stephen I, the 11th century sainted national hero of Hungary, was instrumental in converting the Hungarian people and neighboring tribes to Christianity. We’ll hear Beethoven’s music for the latter play, shorn of its frequently-performed overture.

Eleven years later, the composer was enlisted to provide music for the reopening of Vienna’s Theater in der Josefstadt. For the occasion, the theater’s director, Carl Friedrich Hensler, recalling the success of the Pest double-bill, requested a revival of “The Ruins of Athens.” Beethoven offered to revise the existing numbers and compose new ones to Hensler’s specifications. The result was “The Consecration of the House.”

A new text was provided by Carl Meisl, about whose talents Beethoven was less than enthusiastic. Meisl’s occasional poem describes an exchange between the actor Thespis and the god Apollo and contrasts Greece under the Ottoman Turks to the freedom of Vienna. A chorus celebrates dance, altars are decorated for the entry of the Muses, and the work ends with the obligatory chorus, “Heil unserm Kaiser.” Beethoven wrote a new overture for the piece, which is performed fairly frequently, but for our purposes it will be omitted to allow time for some of the lesser-heard numbers.

Can anything about Beethoven truly be described as incidental? We’ll set aside the symphonies and concertos, for a revelatory evening at the theater with the Master from Bonn. Beethoven treads the boards on “Beethoven, Incidentally,” this week on “The Lost Chord,” now in syndication on KWAX, the radio station of the University of Oregon!

Remember, KWAX is on the West Coast, so there’s a three-hour difference for the Trenton-Princeton area. Here are the respective air-times of my recorded shows (with East Coast conversions in parentheses):

PICTURE PERFECT, the movie music show – Friday on KWAX at 5:00 PACIFIC TIME (8:00 PM EST)

THE LOST CHORD, unusual and neglected rep – Saturday on KWAX at 4:00 PACIFIC TIME (7:00 PM EST)

Stream them here!

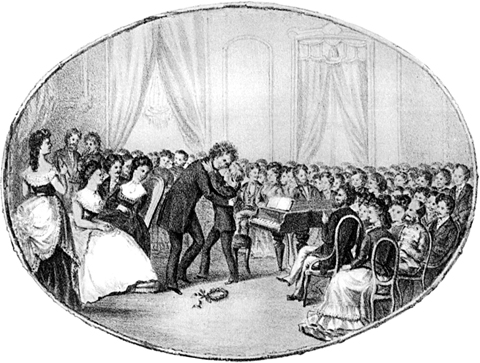

Eleonore Prochaska (left) and the birthday boy from Bonn