This is a good season for John Williams’ concert music, at least where I live. I’m not talking about his film scores, which are likely being listened to somewhere in the world every day. I’m talking about his concertos, of which he has composed many, beginning with the Flute Concerto of 1969. My personal favorites are his first Violin Concerto (in its original version of 1974-76), the bassoon concerto “Five Sacred Trees” (1995), the Cello Concerto (1994; still undecided between the original and revised versions), and the Trumpet Concerto (1996).

I’ve been lucky enough to attend performances of the revised Violin Concerto, the Cello Concerto (in both versions), and Violin Concerto No. 2 (2021) on concerts of the Philadelphia Orchestra. However, the first one I ever actually heard was on the radio, when the Tuba Concerto (1985) was included on a broadcast of the Cleveland Orchestra. Somehow, over 40 years later, I have never heard it live.

This is perhaps the most immediately appealing of Williams’ concertos for those who enjoy his film scores. The first movement, especially, shares some of the wide-open exuberance of, for instance, the lighter moments in “Jaws.” So it is with some pleasure that I look forward to finally hearing it on Friday afternoon on a concert of the Philadelphia Orchestra, with principal tubist Carol Jantsch.

The performance will take place at Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. Also on the program will be Julius Eastman’s Symphony No. 2 and Felix Mendelssohn’s “Italian” Symphony. Dalia Stasevska will conduct.

Friday afternoon no good for you? The program will be repeated on Saturday at 8:00. The Tuba Concerto and “Italian” Symphony will also be performed, without the Eastman, as part of the orchestra’s Happy Hour Concert series on Thursday at 6:30. Get there at 5:00 for pre-concert specials on food and drink and free activities. Happy Hour concerts are followed by post-concert talks with the artists.

I’m also locked in for Williams’ new Piano Concerto, given its premiere this past summer at Tanglewood. Soloist Emanuel Ax will be bringing it to the New York Philharmonic for four performances at Lincoln Center’s David Geffen Hall, February 7-March 3. Also on the program will be Ralph Vaughan Williams’ “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” and Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s Symphony 5. Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla will conduct.

As a little cherry on top, I hold a ticket to a Philadelphia Orchestra concert on May 1 that will open with a suite from Williams’ “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” I don’t generally like Williams’ arrangements of his film scores for the concert hall. There are exceptions, but I don’t think he’s always the best at distilling what makes his movie music so magical, beyond the recognizable themes, and translating it for use on symphony concerts. This is frustrating, because the music is excellent, as it was written, and I do wish it could be worked into something more along the lines of “The Firebird Suite.” A lot could be done with 20 minutes. Williams takes 10.

Anyway, it’s on the same program with Aaron Copland’s Symphony No.3 and, in between, Matthias Pintscher’s “Assonanza” for Violin and Orchestra. Leila Josefowicz will be the soloist, and Pintscher himself will conduct. There will be three performances, April 30-May 2.

I am only in the last 35 pages or so of Jane Austen’s “Persuasion,” which I picked up dutifully to honor the 250th anniversary of her birth. I really want to knock it out today, because I’m dying to start the new John Williams biography by Tim Greiving, a 640-page doorstep issued by Oxford University Press.

February 8 will mark the composer’s 94th birthday. Williams is said to be at work on the score for Steven Spielberg’s upcoming extraterrestrial opus “Disclosure Day,” which has been slated for a June 12 opening.

Tag: Philadelphia Orchestra

-

A Convergence of John Williams Concert Music

-

The Philadelphia Orchestra and Mark Twain’s Daughter: One Degree of Separation

Happy birthday, The Philadelphia Orchestra! Looking pretty good for 125.

The Fabulous Philadelphians gave their first public concert under Fritz Scheel on this date in 1900. The event took place at the orchestra’s former home of the Academy of Music, located on the southwest corner of Broad and Locust Streets. On the program were works by Carl Goldmark (“In Spring” Overture), Beethoven (Symphony No. 5), Tchaikovsky (Piano Concerto No. 1), Weber-Berlioz (“Invitation to the Dance”), and Wagner (“Entry of the Gods into Valhalla”).

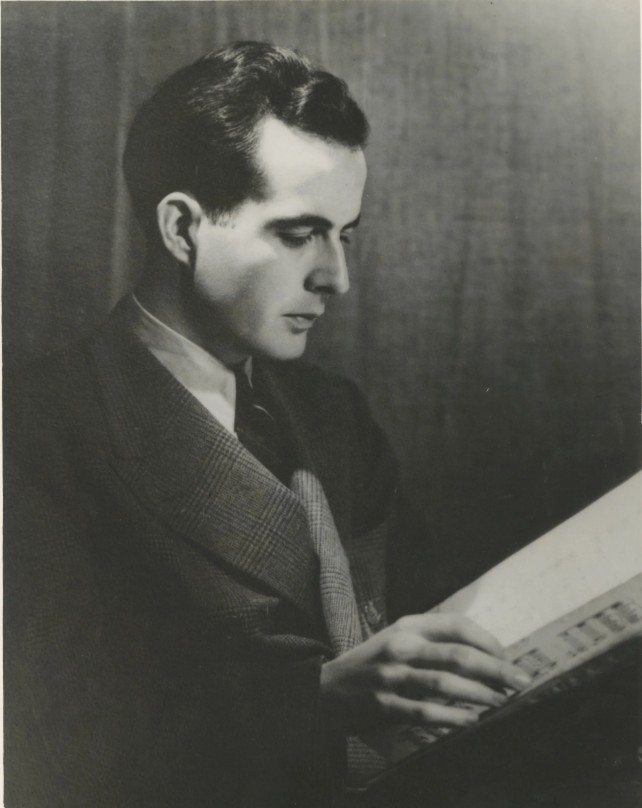

The soloist on that occasion was Ossip Gabrilowitsch. Gabrilowitsch’s teachers at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory included Anton Rubinstein and Nikolai Medtner. He then studied for two years in Vienna under the legendary pedagogue Theodor Leschitizky. Not only was Gabrilowitsch a prominent pianist, he was also offered the music directorship of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which he politely declined. Later, he became founding director of the Detroit Symphony in 1918. He was also Mark Twain’s son-in-law. In my possession is a biography I picked up for $3 at a public library sale, “My Husband, Gabrilowitsch,” that I noticed had been inscribed by Twain’s daughter, Clara Clemens!

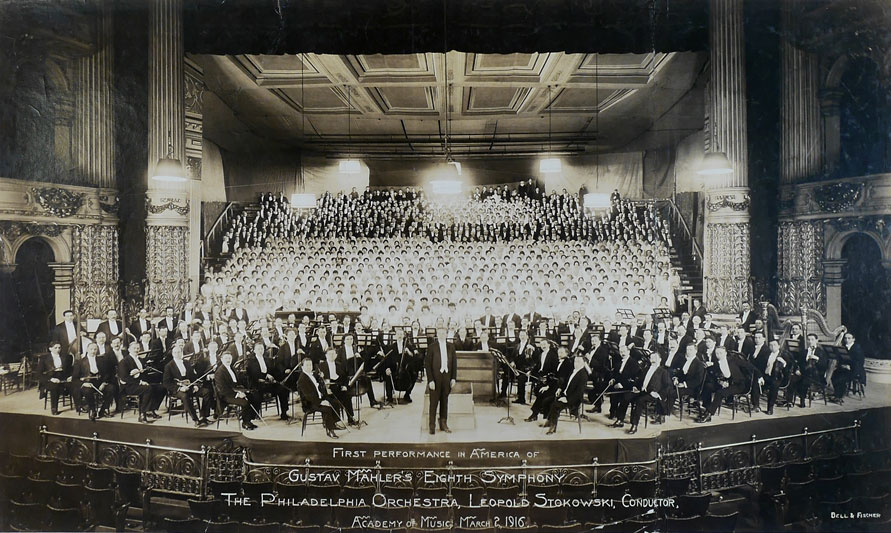

Fritz Scheel was succeeded as music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra by Carl Pohlig in 1908. Leopold Stokowski (pictured) followed in 1912; Stoky would lead the group for the next 24 years. Then came Eugene Ormandy, who held the podium until 1980 – 44 years. Ormandy passed the baton to Riccardo Muti, who directed from 1980 to 1992. Muti was followed Wolfgang Sawallisch, who remained with the orchestra for the next decade. Sawallisch was succeeded by Christoph Eschenbach in 2003. Eschenbach was followed by Charles Dutoit, appointed “Chief Conductor” in 2008. And, bringing us up to the present, Yannick Nézet-Séguin arrived, with vitality to burn, in 2012. What a history!

Since I lived in Philadelphia for over three decades, this was my resident orchestra. I saw many of the greats there, with some particularly unforgettable nights at the Academy of Music, especially when I was in my 20s. Also in the summers, at the Mann Center in Fairmount Park, when the orchestra played three or four different programs a week. A lot of those artists aren’t around anymore. I have some cherished memories of the orchestra at its current home at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, too, but perhaps inevitably I view those earlier concerts through rose-tinted glasses, halcyon experiences preserved in the amber of my youth. It’s astonishing to realize that I have been attending concerts with this ensemble over a span of 41 years! It’s been an indispensable part of my life.

Thank you, and a happy 125th, Philadelphia Orchestra!

—————

A great read about Clara Clemens and Ossip Gabrilowitsch in the Star-Gazette of Elmira, NY

https://www.stargazette.com/story/news/local/2024/03/08/mark-twain-daughter-clara-clemens-studied-music-performed-in-elmira/72775353007/

The Twain plaque was stolen from a joint monument dedicated to the author and Gabrilowitsch at Elmira’s Woodlawn Cemetery, but returned, in 2015

https://www.syracuse.com/state/2015/09/mark_twain_stolen_plaque_returned_to_tomb.html

An account of Gabrilowitsch, guest conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra, addressing the audience on the subject of applause. (He was in favor of it; apparently Stokowski was not.)

https://www.nytimes.com/1930/02/01/archives/gabrilowitsch-urges-audience-to-applaud-takes-issue-with-stokowskis.html

—————

PHOTO: Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Academy of Music in 1916, ready to go for the American premiere of Gustav Mahler’s “Symphony of a Thousand” -

Wagner’s “Tristan”: The Agony and the Ecstasy

At the conclusion of Sunday’s marathon performance of Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde” by the Philadelphia Orchestra, after having been stretched on the rack for five hours, the elastic finally snapped. Spine and scalp were atingle with the thrilling Romantic sublimity of it all, as Isolde clears that final, hysterical hurdle to ecstasy and death with the Liebestod.

But that’s the magic of “Tristan,” surely the most extreme example of deferred gratification in the repertoire. And by the time that gratification is achieved, most everyone is dead. And the audience is not spared. It’s classical music’s equivalent of making love to a praying mantis. No matter how flippant I can be about “Tristan,” it exists on a very high plain, perhaps the highest. The greatest works of art can tear a hole in the fabric of the world and reveal the emotional truth of existence. They tap into something primal and irrational and leave you shaken to the core. On Sunday, the work hit me with three times its usual power. And I live to tell the tale.

Of course, there was Wagner’s music, achieving apotheosis and release at the end of five glorious hours of portentous woodwinds and passionate, seething strings, and superhuman voices cresting terrifying waves of sound.

Then there was the audience reaction, which could only be described as ecstatic. All three acts were greeted with volcanic applause, but the final curtain was received most rapturously, with the lava flowing long and lovingly, and deservedly so.

Either one of those in themselves would have been enough to wreck me, but the performance also marked Nina Stemme’s farewell to the role of Isolde, a part she sang to great acclaim for a very long time, and she was visibly moved, wiping away tears at the end. I’m getting choked up now, nearly two days later, just thinking about it. There’s something to be said about going out on top, but Stemme, at 62, was so powerful and secure, with perhaps only two or three times where she might have landed a tad sharp on a high note (I do not have perfect pitch), but she kept her toes near the chalk and sang with adamantine strength. I was totally in love with her.

Her partner, Stuart Skelton near-matched her in power as Tristan (though perhaps not quite), and he was in good voice throughout, but I feared for his stamina. Skelton is a big man, to put it mildly. He was the elephant in the room, both figuratively and near-literally. Later, I found an interview with him on YouTube, in which he speaks of how every part of the body serves a function in terms of creating a singer’s unique resonance, but there’s got to be a compromise so that those of us in the audience don’t worry about witnessing someone’s imminent collapse. But perhaps my concern was misplaced, as over three hours in, he still had plenty of power in reserve for Tristan’s mercurial highs and lows in Act III. Wagner must be the one branch of opera wherein the old stereotype of the gargantuan singer endures. At least in a staged production, they could have thrown some furs on the guy, or given him a winged helmet. Kurnewal’s remark about having carried him ashore brought a moment of unintended comedy (for me), only to be surpassed, when in supposed death, Skelton reached into his vest pocket and popped a lozenge or perhaps a nitroglycerin pill. All respect to your artistry, sir, but for godsake, do take care of yourself!

The orchestra’s music director, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, ever stylin’, conducted in what looked like a synthetic t-shirt, long-sleeved with a kind of Nehru collar and French cuffs, that had been tossed in the wash with some black towels. And of course, he wouldn’t be caught dead without his Louboutins. Yannick gonna be Yannick. Sartorial choices aside, he conducted with muscle and vigor throughout. I guess his workout routine in the tongue-in-cheek video used to market these performances really paid-off.

It took a few minutes for the Prelude to start weaving its magic as it should, but it wasn’t long before I was in the music’s thrall. Regardless of what you may think about the depth of this guy’s performances, he is a magnetic conductor.

The orchestra musicians themselves played with great commitment, some really throwing themselves into it. Principal double bass Joseph Conyers was right in my sightline, and he really dug in and played with exuberance and zest. Wagner gives his musicians plenty to enjoy, whether it’s to claw at your heart, reach for the ineffable, or imitate burbling fountains.

“Tristan und Isolde” is like a narcotic. Is there any other piece of music that can so alter one’s consciousness? It both depresses and inflames the listener. It’s like spider venom. But what ecstasy! I’m sure I’m not the first to observe, it can’t be good for you.

Moreover, the whole Romantic fascination with love-death is so deeply unhealthy, but in my abnormally-prolonged youth I embraced it to the hilt. How I ever made it to my 50s is anyone’s guess. Act II made me remember every love affair I ever had – ardent, reckless, and doomed.

The stage performance lacked sword fights and poisoned chalices, but Skelton and Stemme held hands and touched foreheads during the love scenes. For the most part, the singers were positioned on a scaffold behind the orchestra, accessible from the stairs of the “Conductor’s Circle” (seating near the organ loft at the back of the stage), but occasionally they popped up unexpectedly on other tiers. I was enraptured being so close to Karen Cargill, her Brangäne keeping watch over the lovers in Act II, as she sang, hypnotically, only yards from my box. I jotted down one word: BLISS! Likewise, members of the orchestra were sent around the hall and backstage to achieve certain spatial effects. English hornist Elizabeth Starr Masoudnia had a plum part, doubling for a shepherd’s pipe and sharing the scaffold with Tristan and his wingman, Kurwenal.

Cargill was a standout among the supporting cast. Brian Mulligan, as Kurwenal, was another. But the singer who perhaps best inhabited his role, in terms of balancing the demands of voice and action, was Tareq Nazmi as King Marke, whose embodiment of the part transcended the requirements of a concert performance. His rounded portrayal drew real sympathy for the character, who is not only king, but Tristan’s uncle, come to regard the younger man as his son. Nazmi sold the realism of a betrayed, baffled, and ultimately beneficent king. If anything, it made the Friar Laurence moment of his too-late-arrival all the more poignant. Then again, no one told Tristan he had to tear off his bandages.

The opera spanned close to five hours, with two 25-minute intermissions. For the first of those I hurried down the elevator and weaved across the lobby like a running back, bypassing the concessions crowds with a dash across Broad Street to the Good Karma Cafe, adjacent to the Wilma Theater, for a medium coffee. This I supplemented with doughnut holes from a tiny Tupperware I’d smuggled from home. Once during the first act I caught myself nodding and I was afraid I might tumble right over the railing. During the second intermission, I kept my energy up by eating a banana.

Before the start of the performance (at 2:00), I couldn’t help but smile to myself as I glanced down the rows of seats in what pass for boxes in Philadelphia. The Third Tier is the Lonely Guy tier. Predominately bachelors and social misfits. Always like this wherever I go, come to think of it, with whatever I happen to enjoy. What does that say about me, I wonder? The guy in the box in front of me showed up in shorts carrying a hardbound copy of the score, which he followed most assiduously, seldom looking up for most of the first act. He disappeared for the rest of the opera. I hope it was to find a better seat. The guy behind me slipped out during the third act. I turned around, and he was gone well before the Liebestod. Did he lack the stamina, or was he hoping to avoid the traffic? I never understand people who go to a concert and then dash off before the end to beat the crowd to the garage. Kind of defeats the purpose of even attending.

One thing that impressed me was – an unfortunate, unmuffled cough at the beginning of the Prelude aside – the audience was unusually and blessedly quiet throughout. Yes, there were coughs, very occasionally, but none of those annoyingly ostentatious gotta-cough-for-the-sake-of-coughing coughs. And no cell phones! Wagnerites are a different breed. Don’t attempt to desecrate their temple.

I would have loved to have seen this “Tristan” staged, but in making it a concert performance, at least the audience was spared the Regietheater excesses that mar so many Wagner productions these days. Here, the music was allowed to speak without any sideshow distractions. I will remember Stemme’s Isolde for a long time. Were there moments when she was lost in the wash of sound? Believe me, they were few. I know I’m mixing my Wagner music dramas, but she had the vocal power of a Valkyrie. I count myself very fortunate to have experienced her instrument live.

It was instructive to attend this performance two days after having heard Richard Strauss’ “Guntram” at Carnegie Hall on Friday. I’m hoping to write that up tomorrow for Strauss’ birthday.

In the meantime: bravo, The Philadelphia Orchestra! Truly, this was a transformative event.

Tag Cloud

Aaron Copland (92) Beethoven (94) Composer (114) Conductor (84) Film Music (106) Film Score (143) Film Scores (255) Halloween (94) John Williams (179) KWAX (227) Leonard Bernstein (98) Marlboro Music Festival (125) Movie Music (121) Mozart (84) Opera (194) Picture Perfect (174) Princeton Symphony Orchestra (102) Radio (86) Ross Amico (244) Roy's Tie-Dye Sci-Fi Corner (290) The Classical Network (101) The Lost Chord (268) Vaughan Williams (97) WPRB (396) WWFM (881)