The trailer for Ralph Fiennes’ new film, “The Choral,” which I’ve been seeing over the past month or so, whenever I go to the movies, has proved to be a bit of a bait and switch. An English period piece set during World War I, it appeared, from the marketing, it would be an inspirational story about the power of music.

Yeah, the war was a bad time, lives were destroyed, and the flower of England’s youth mowed down at the Somme. But the trailer features just enough humor to make it seem like something it’s not. I caution you not to go into it expecting a charming story of idiosyncratic British resourcefulness in the tradition of “The Full Monty,” “Kinky Boots,” or “Calendar Girls.” I’d have been happy had it been “Chariots of Fire” meets “Brassed Off.” (The latter is about England’s colliery brass bands; “The Choral” is about its amateur choral societies.)

Primarily, I got the impression that the film was going to explore musical performance as a kind of therapy for damaged soldiers returning from the front, but it really does nothing of the sort, beyond the suggestion being made in one scene, and then it’s never revisited.

Fiennes is excellent as always, as the displaced, disgraced choral director forced back to England from a satisfying career in Germany, on account of the war. His scrupulous German allusions and quotations from passages of Goethe and the “St Matthew Passion” (which the English of course sing in English) do nothing to endear him to the locals, who view his foreign connections with suspicion. After a rock comes crashing through a window during a rehearsal, it is suggested perhaps the choir should sing something else. It is to the choristers’ collective dismay that they realize that every composer they offer happens to be German – even honorary Londoner George Frideric Handel.

This is when “The Choral” pulls its rabbit out of the hat, and we discover that the rest of the film will center on an amateur performance of Elgar’s “The Dream of Gerontius.” What a very happy surprise!

Alas, the happiness is short-lived. Naturally because of the war, budgetary constraints, and not least the varied ability of the singers, concessions have to be made. The result is a “bold” reimagining of the oratorio that seems about as edgy as something out of “Dead Poets Society.”

Inevitably, Elgar shows up, and both his character and the casting (he’s played by the estimable Simon Russell Beale) are totally wrong. Nothing I have ever seen or read about Elgar leads me to believe he was squat, portly, and petty. Couldn’t the filmmakers even have given him a decent push broom mustache?

Perhaps it won’t bother viewers who aren’t so close to the subject, but for me it kills the movie. My guess is that the marketers kept the “Gerontius”/Elgar angle out of the trailer, because there are about five people in the U.S. who would have any idea who or what they are, much less want to see a movie about them.

More broadly, the screenplay by playwright Alan Bennett (“The Madness of George III,” “The History Boys”) is a mess, with few of the many dramatic ideas introduced in the first act (war trauma, suspicion of espionage, wounded vanity and squabbles among the singers, betrayal in love, an interracial romance that never raises an eyebrow, the plight of the homosexual and the conscientious objector in 1916) are ever satisfactorily resolved.

Like real life, then? I think it was just weak. Still, hats off to Bennett for writing another screenplay at the age of 90!

Bennett is clearly interested in English music. He wrote a play, “The Habit of Art,” about the relationship between W.H. Auden and Benjamin Britten. Ursula Vaughan Williams (Ralph’s widow) was a personal friend and appears as a character in “Lady in the Van.” So I am especially sorry that this late attempt to dramatize the import of Elgar and his music is a swing and a miss. Perhaps with a different actor. If only C. Aubrey Smith were still with us!

“The Choral” is not a bad movie. As a classical music lover, I would desperately like a film of this sort to succeed. However, if like Fiennes’ choral director I’m to be brutally honesty, I must acknowledge that it fails to hit any of the high notes.

——–

View the trailer here:

Category: Film Reviews

-

“The Choral” Misses Its High Notes

-

Bergman’s Enchanting “The Magic Flute”

From time to time, I guess even Ingmar Bergman needed a break from existential dread. How else to explain his delightful adaptation of “The Magic Flute?” Originally intended for television, Bergman’s playful and inventive 1975 film of Mozart’s 1791 singspiel had a lot to do with setting me on the path to become an opera lover.

The conceit, to set the action as a live performance in the historic Drottningholm Palace Theater (a reproduction, since there were concerns about the actual theater safely accommodating a film crew), is disarming and inspired. All the stagecraft is laid bare. The scenery is evidently painted plywood, the animals are all people in suits, and the characters pause from time to time to hold up little signs with moralistic aphorisms on them as they sing their arias.

Bergman’s film begins outside the actual theater and then enters the hall during the overture to register the facial expressions of a audience members as they anticipate the curtain rising. Most especially the camera lingers on the eager face of an impressionable young girl. It’s evident that the director would like us to experience it all from her perspective, through a lens of innocence.

By contrast, we’re also taken backstage, to glimpse Papageno, fallen asleep and nearly missing a cue, Sarastro between acts studying the score to “Parsifal,” and one of Monostatos’ minions reading a Donald Duck comic book.

Sure, there are moments of despair even here, as a couple of the characters contemplate suicide (we also get a memorable vision of hellfire), but it’s all dispelled in a decisive victory of good over evil, an endorsement of universal brotherhood, and a resolution of unalloyed joy.

It was Mozart’s librettist, Emanuel Schikaneder, who suggested during rehearsals that Papageno stammer in excitement at the recognition of his desired Papagena, in their famous duet. Here’s what Bergman does with it.On Mozart’s birthday anniversary, I think it’s time to revisit this film.

Behold! Here it is on YouTube.

-

“Blue Moon” Sings

It’s got to be Oscar season. It’s rare for me to see two movies I liked – I mean, really enjoyed – in one week. (Read my impressions of Guillermo del Toro’s “Frankenstein” from November 6.) I mean, I don’t generally make the trek to a theater to see anything I know is going to be trash anymore – unless it’s “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny” (ouch!) or “Megalopolis.” “Blue Moon” is on a more intimate scale, but quietly thrilling in a way neither of those enormously-budgeted films were.

Local hero Ethan Hawke, who grew up in West Windsor, NJ, and hung out in Princeton – where he attended the Hun School and gained early acting experience at McCarter Theatre – plays the acerbic, needy, soulful, brilliant lyricist Lorenz Hart, smarting from the fledgling success of his longtime creative partner, composer Richard Rodgers, on the opening night of “Oklahoma!” – Rodgers’ inaugural effort with Oscar Hammerstein II. Hart, the wound of rejection oozing like sour grapes through all the malbec and bourbon, delivers rapid-fire, barbed arias and elevated panegyrics to ineffable beauty – unsurprisingly, given his vocation, always lighting on the “mot juste.” He observes that any show that ends in an exclamation point isn’t worth seeing. He’s hard on “Oklahoma!’s” middlebrow success (and I can’t say that I disagree). He thirsts for art that’s more inventive, more challenging, one that takes creative chances. He bristles at facile lyrics such as corn that’s “as high as an elephant’s eye,” as all good folk should. Except, of course, the beauty of what Rodgers & Hammerstein achieved at their best also defies logic.

Hart was no slouch either, if exasperatingly difficult to pin down. It’s made abundantly clear that he had to be a nightmare to work with, especially for someone as disciplined as Rodgers, with his regular work habits. By contrast, Hart enjoys the pleasures of distraction and dissipation, staying out after-hours and sleeping until noon. You couldn’t find a better example of clashing personalities sharing an inexplicable chemistry, although of course such bonds are abundant in the history of the creative arts. We’re reminded from the start that the Rodgers & Hart partnership yielded a thousand songs, including “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered,” “My Funny Valentine,” “Isn’t It Romantic,” “The Lady is a Tramp,” and the titular “Blue Moon.” The soundtrack is a juke box for admirers of the golden age of the American Songbook, with the soundtrack pretty much wall-to-wall Richard Rodgers, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, and George Gershwin.

There are running gags about “Casablanca,” as Hart banters with Eddie the bartender (Bobby Cannavale), an earthy but sympathetic foil, and in-jokes about Stephen Sondheim and “Stuart Little.” E.B. White (Patrick Kennedy) happens to be sitting in a corner booth. There’s also a plum role for Magaret Qualley, as the self-described “ambisexual” Hart’s statuesque, 20-year-old muse. There’s an extended conversation in a cloakroom that allows both actors to really shine.

Hawke, who in life is 5’ 10” with a full head of hair, disappears into the character, made to appear physically diminutive, sporting a combover and double-breasted suit, and for much of the movie, swilling booze and chomping on a monstrous cigar. (In the old days, Hart could have been played by Lionel Stander.) The illusion is broken only in a couple of shots, when he’s shown wearing a hat in profile, which obscures the make-up, and we can’t help but notice that it is indeed Ethan Hawke. Otherwise, the magic is sustained for 100 mesmerizing minutes.

The film is directed by Richard Linklater, who’s written and/or directed mostly modest yet persistently memorable movies, including “Slacker,” “Dazed and Confused,” and “School of Rock.” I’m not by any means a rocker, but I do have a soft spot for the Jack Black opus, which I still find myself quoting often. (I too have lived the legend of the rent.) Also, the trilogy of films starring Hawke and Judy Delpy that began with “Before Sunrise.” And the even more ambitious “Boyhood,” shot in installments over 12 years, so that the actors (including Hawke, but especially the young Ellar Coltrane, who plays his son) could age in real time.

Despite taking place largely in one location (the legendary theatrical hangout, Sardi’s), “Blue Moon” is more rapid-fire, with enough dialogue for four or five movies, and I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised if it takes on a second life as a play. The screenplay is by Robert Kaplow, whose book, “Me and Orson Welles,” Linklater shepherded to the screen in 2008. The dialogue is very good – smart, often acrobatic, but always believable – and the actors stick every line.

There’s a moment when Hart holds Rodgers (Andrew Scott, no less excellent) back from an upstairs reception and the two men – Rodgers now at the peak of his career and Hart sensing he is at the end of his – stand on a landing together, cycling through a gamut of emotions that color their complex personal relationship, with its shades of friction, annoyance, exasperation, and underlying affection. It is some finely tuned and nuanced work, those emotions flitting across their faces and reflected in their body language as subtly as wisps of cloud on a sunny day. Anyone who’s lived long enough has surely experienced similar moments with a complicated friend or family member. The movie is full of such touches, which stand in absorbing contrast to Hart’s alcohol-propelled bluster.

I’ve been meaning to get around to seeing this, which I had been anticipating ever since I saw the trailer weeks ago, but I missed it in Princeton, where it had a very short run. But I was able to catch it up Route 206 at Montgomery Cinemas (where, by the way, “Frankenstein,” is also still playing). My stepfather saw it a week or two ago, and he brought it up during our most recent telephone conversation, knowing what a music guy I am. We always talk movies. We’ve done so our entire lives, and I know he gets a kick out of it, probably in large part because I still know who people like Lionel Stander are. He said he’d tell me what he thought of it once I had a chance to see it. He didn’t want to color my impressions of it, he said. To me, that suggests he was lukewarm on it. One of his most-hated experiences in a theater was viewing “My Dinner with André” (which I also really like), which is basically André Gregory and Wallace Shawn conversing at a table in a restaurant for two hours. I could see how, for him, this movie might have a touch of that, but I would think also that there are just so many period references – he’ll recognize Sardi’s and “Casablanca” and the American Songbook, even if he might not pick-up on E.B. White and Sondheim – he would at least got some enjoyment from it. I guess I’ll find out.

Anyway, I wouldn’t be surprised if there are Academy Award nominations for Hawke, who’s come a long way from “Dead Poets Society,” and screenwriter Robert Kaplow.

It’s the rare movie about music that I actually like. I feel like “Blue Moon” actually gets it right, largely because it avoids the Scylla and Charybdis of, on the one hand, attempting to portray the mystifying act of creation (a mostly internal, undramatic process), and on the other, attempting to define the ineffable (a word Hart really likes) essence of music.

“Blue Moon” works as a character portrait of a fictionalized Hart, with just enough supporting players and good performances to make this pocket-dramedy sing. -

“Frankenstein”: It’s Alive

From some of the computer-generated chaos at the start, I was afraid I wasn’t going to like Guillermo’s del Toro’s “Frankenstein.” I guess I’m still smarting from Robert Egger’s remake of “Nosferatu.” But here my concerns were misplaced. As writer and director, Del Toro definitely puts his own spin on the source material, yet he manages to honor Mary Shelley’s 1818 classic. More importantly, the movie is full of heart. I don’t want to get anyone’s hopes up, but I wound up actually really liking it.

I hasten to add, Del Toro’s approach is more Shelley than Karloff, even though he turns a lot of the original novel on its head. Don’t go into it expecting any “scares.” This is a movie that explores the nature of humanity and man’s overweening desire to push into the unknown without considering the morality of doing so or assuming responsibility for the consequences. It is, after all, “Frankenstein.”

But these underpinnings are not simply brushed aside so that the filmmakers can get on with the killings, as is the case with so many of the movies. It has one of two gruesome moments, for sure, but the lens doesn’t linger. Rather, it is a thoughtful, literary, even philosophical movie, with layers of allusions and symbols that fit hand-in-surgical glove with the narrative.

Oscar Isaac plays the haughty, frustrating scientist, Shelley’s “modern Prometheus,” as maddening as he is mad. His rearing of his creation proves here to be the product of cyclical abuse. The theme is skillfully assimilated and has a nice payoff. Tragedy is woven right into the story, of course, but this is one Frankenstein movie that actually leaves one with a glimmer of hope. Del Toro has loved this story – and “the creature” – since childhood, and clearly he’s internalized everything. Like Victor Frankenstein himself, he’s discovered the source of its life; but unlike Victor he also recognizes its soul.

I have no idea who Jacob Elordi, who plays the creation, is, but he is a wonder. His performance makes the movie. I note he’s also going to be playing Heathcliff in an impending, overheated adaptation of “Wuthering Heights,” with Margot Robie trading on her “Barbie” good will. From the trailer, it looks as if it totally misses the point of Emily Bronte’s novel. But here, Elordi is excellent. As with “The Shape of Water,” Del Toro proves that he can be much more than simply a technical director, eliciting fine performances from his leads.

That said, I would be remiss if I didn’t also mention how sumptuous a production this is. Every detail is fully realized, from the vibrant costumes to the outrageous and eyepopping sets, digital or otherwise. The lavish estates, the streets of Edinburgh, the frozen battlefields, the Thomas Eakins medical theater, the steampunk lab, and the arctic wastelands all look fabulous, often operatically stylized, but all of a piece. The production design more than compensates for a few moments of shaky CGI, with cartoonish flying bodies and pouncing wolves.

Why, oh why, aren’t they making it easier for people to see this in a theater? This practice of showing a film for a very limited run in just a few venues so that it qualifies for Academy Awards consideration before consigning it to streaming on Netflix as “content” is more monstrous than anything in the movie.

Beyond the all-too-rare experience these days of enjoying the film on a big screen with an engaged audience, it was such a pleasure to be able to sit there during the end credits and to be able to ruminate on what I had just witnessed to Alexandre Desplat’s evocative score. That is a part of the moviegoing experience that is so tragically undervalued in the streaming age. So much of a movie’s impact is cemented in those few minutes at the end, when you just allow it all to sink in.

I hope you will follow my advice and don’t google anything about it, if you haven’t done so already. It’s best to experience it fresh. It’s a beautiful movie, visually and emotionally alive, with good performances, and I highly recommend it.

“Frankenstein” comes to Netflix tomorrow, but if you can see it in a theater, go.

-

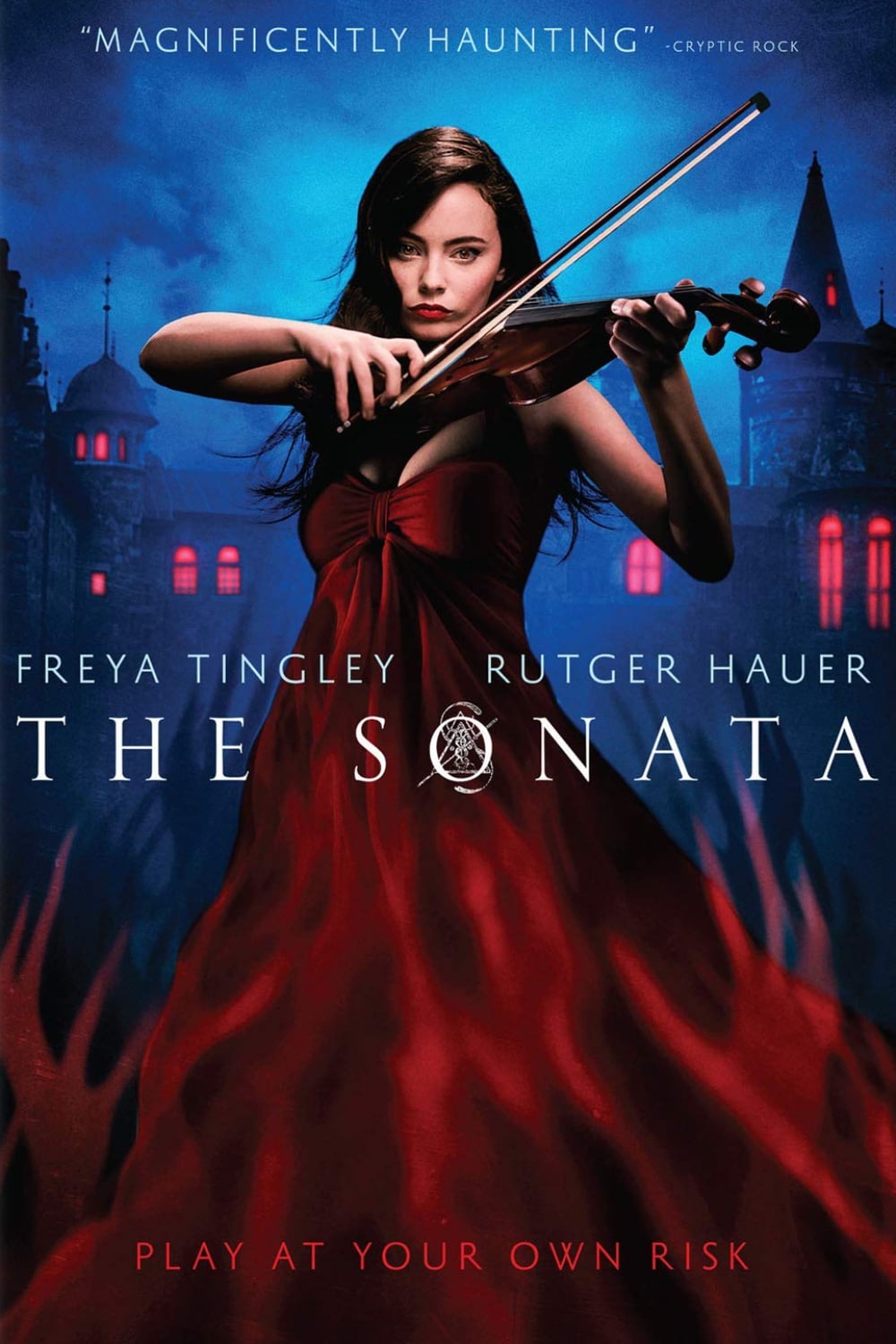

“The Sonata”: Mr. Horror’s Opus

Paganini. Liszt. Warlock. Classical music has plenty of sulfur for anyone looking for Faustian inspiration. If longhair music is your thing, chances are you’ll find “The Sonata” (2018) a hoot. Especially for Halloween.

The film opens with Tartini’s “The Devil’s Trill,” naturally – Satan’s most infamous gift to the field. (It came to the composer in a diabolical dream.)

Rutger Hauer plays a reclusive, disproportionately revered, and somewhat sinister British composer by the name of Richard Marlowe (surely named for Christopher Marlowe of “Doctor Faustus” notoriety). When Marlowe dies by his own hand, we learn from the story’s heroine, violinist Rose Fisher (Freya Tingley), of their secret bond, which sends her to France to leisurely poke around his 11th century château. Discovered in his desk, under lock and key, is his final composition, a violin sonata, that sets Rose’s manager, Charles (Simon Abkarian), salivating.

And here’s where we take one step further into some unintentionally bizarre alternate reality, as Charles actually believes that this discovery is the “big break” he has been dreaming of his entire career. “Rose,” he says, “you do know, if this is your father’s final work, it could be a huge sensation.”

If you’re not scratching your head yet, “The Sonata” is set in a modern world where haunted mansions and medieval grimoires coexist with a widely-relevant classical music culture – where major record labels are still subsidizing recordings by important artists and the discovery of an unknown manuscript by a contemporary composer is enough of a windfall to ensure fame and fortune for those who inherit the copyright and control its promotion. It’s a world where Shostakovich is name-dropped and Yehudi Menuhin is used as a comparative is newspaper headlines. A world where composers are still interviewed on television talk shows. In short, a world that hasn’t existed since the 1980s.

Furthermore, disulfiram hasn’t commonly been used to treat alcoholism since the 20th century. Yet this clearly is not intended as a period piece. In fact, it may be the first film I’ve seen with someone talking on a cell phone in a haunted house.

Director Andrew Desmond, whose first feature this is, evidently picked up a trick or two from Robert Wise, who helmed, for my money, the most chilling of haunted house thrillers, “The Haunting,” made all the way back in 1963. There are low-angle shots of the house, gloomy close-ups of portentous statuary, disembodied children’s laughter, and creepy turning doorknobs. It also reminds me a bit of “The Legend of Hell House” (1973), with the spirit of a departed sadist – in the former, played by Christopher Plummer; in this one, Hauer – looming spookily over the proceedings.

Hauer, whose last completed film this is, only has a minute or two of screen time, but he’s never out of our consciousness, thanks in large part to audio and video recordings (cassette tape… really?) and a portrait that dominates the mansion library. Is anyone really surprised when the old man turns out to be a modern-day Gilles de Rais? Thankfully, Marlowe’s misdeeds are conveyed by way of suggestion, which is more than enough, thank you. And you just know that the sonata, with its arcane symbols sprinkled in amidst the standard notation, is going to be used to conjure the Antichrist.

The film is well-made, with good production values, and on the whole, good acting. James Faulkner is especially fine as an authority on Baroque music and the occult. He does a lot with his one or two scenes, and I wish he had played a larger part, with his authoritative voice and forked goatee. The movie doesn’t go into it, but there really were a lot of artists, writers, and composers tied up in the occult in the U.K. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I know I’ve written about it. I’ll link one of my posts about the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn below.

Abkarian is good too, skillfully navigating a role that requires some spackling over of the cracks in what could have been a much flimsier suspension of disbelief.

A few quibbles from a classical music perspective:

Why is Rose recording Wieniawski’s Violin Concerto No. 1 without an orchestra? If it’s supposed to be at a separate session – for a patch, perhaps? – shouldn’t she at least be wearing headphones?

When Rose discovers Marlowe’s sonata, why does she try it out at the piano instead of picking up the violin that is precariously propped on a chair right next her? Beyond setting us up for a M. Night Shyamalan moment, that is?

How is the violinist Charles consults to assess the unknown sonata able to surmise so much about its content and structure from merely flipping through the score?

Finally, would a professional violinist really allow a taxi driver to unpack her instrument from the trunk of his car?

Fortunately, in a film that places so much emphasis on music, Alexis Maingaud’s score is of a considerably higher caliber than what is usual in movies today, serving as more than just sound design, with an 80-piece orchestra – although at times electronically modified – and actual melodies. (Olivier Leclerc plays Rose’s violin solos.) Amusingly, the composer receives a cameo of sorts: look sharp for his name on the digital display of a sound system as Charles unwinds to some jazzy saxophone music. (Relatedly, the director’s voice can be heard as Marlowe’s interviewer on an archival videotape.)

Best of all is the selection from one of Marlowe’s compositions (played from CD), “The Double Life of Persephone,” which is spot-on for a post-romantic concert piece. If the music isn’t lifted from an actual concert composer, it is wholly convincing, and I for one would like to hear more! The title suits the film thematically, of course, as Persephone, the Queen of Hades, spends half her time in the underworld.

In an interview I turned up (an actual interview this time, as opposed to a fictional one), Maingaud confesses his admiration for Jerry Goldsmith. Bernard Herrmann too is mentioned. So his head is in the right place. A former classmate of the director at Sorbonne University, he is also fairly close to the start of his career. I hope to hear more from him and that he doesn’t just disappear the way his compatriot, the French composer Ludovic Bource, seems to have done, in this country anyway, after winning an Academy Award for his music for “The Artist” (2011).

By now, we all know the Gothic tropes and trappings of the old, dark house. The fixtures are mahogany, the keys are iron, and the lofty staircases navigated by candelabra. How many times does the heroine have to soak in a leisurely bath, in a clawfoot bathtub by candlelight, in a big “empty” manor, or wander the stairs in a silk peignoir? There are a few scenes, especially one in which Rose explores a grotto by striking matches that make me wonder why she doesn’t simply use the flashlight function on her cell phone.

To his credit, Desmond leans into slow-burn mystery and atmosphere, which personally is what I really value in a ghost story. But horror cliches abound and the manufactured jump scares become more risible (with the exception of one or two) as the film progresses. Most of them seem as if they might have been afterthoughts, dreamed-up in post-production and achieved by inserting musical stings and sound effects.

Then, just when I fully believed Desmond had learned his lesson well – that the less seen, the scarier the unfathomable becomes – he drops his cards to the floor and blows it in a climactic scene that must be the biggest letdown in a movie of this sort since “The Ninth Gate” (1999). This is one film that could have done without the CGI. I was hoping for something a little less literal and a little more… uncanny.

But hey, if your flawed film is being compared to Roman Polanski, it’s still something to be proud of. If you don’t remember, “The Ninth Gate” dealt with Satan and rare books. It’s been a quarter century since I’ve seen it, but I think I like this movie better.

With a stronger ending, “The Sonata” could have become a wink-and-a-nudge Halloween classic for classical music folk. Still, I’d be lying if I were to say I didn’t enjoy being seduced into this fantasy world where books and music are treated as matters of life and death.

I got an additional chuckle out of it, as there is also the grave revelation of a secret society devoted to the dark arts that calls itself the Famulus Order. Famulus was the name of the book business I ran in Philadelphia for 13 years. (I’m only just now noting the numerical significance!) And yes, my logo was ripped from a 17th century woodcut of some guy in Elizabethan breeches swapping books with the Devil.

Unfortunately, after leading us down a lot of compelling, creepy corridors, “The Sonata” drops us at a dead end. With the big build-up and weak fizzle, I couldn’t help but think of another film, one starring Richard Dreyfuss, from about 30 years ago, that pretty much did the same thing, teasing the audience and building expectations for a climactic musical masterpiece, the protagonist’s life’s achievement, which in the end turns out to be a three-minute wet noodle. In the case of “The Sonata,” they might just as easily have called it “Mr. Horror’s Opus.”

“The Sonata” is streaming free on Amazon Prime and Tubi and, for all I know, elsewhere. It’s a fun movie for classical music fans; just not the enduring genre favorite it could have been.

Interview with composer Alexis Maingaud

One of my posts on occultism and English music

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1193772614875133&set=a.883855802533484

Tag Cloud

Aaron Copland (92) Beethoven (94) Composer (114) Conductor (84) Film Music (106) Film Score (143) Film Scores (255) Halloween (94) John Williams (179) KWAX (227) Leonard Bernstein (98) Marlboro Music Festival (125) Movie Music (121) Mozart (84) Opera (194) Picture Perfect (174) Princeton Symphony Orchestra (102) Radio (86) Ross Amico (244) Roy's Tie-Dye Sci-Fi Corner (290) The Classical Network (101) The Lost Chord (268) Vaughan Williams (97) WPRB (396) WWFM (881)