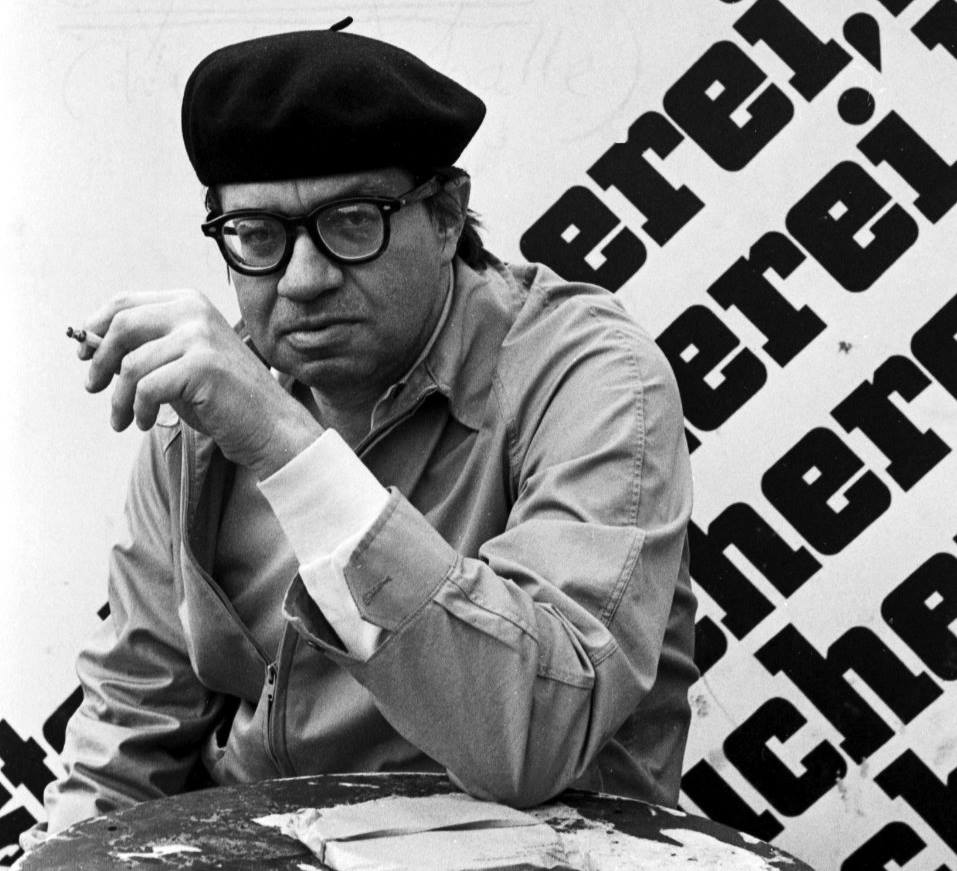

When I think of Morton Feldman, the first thing that springs to mind is a Summer Solstice event I attended at Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts in 2007. This was an all-night, multidisciplinary, festive affair that included music from across genres, a dance hall with live bands (observers gazing down from the balconies of a converted Perelman Theater), opera, cabaret, karaoke, hip-hop, jazz, juggling, Irish and Hindustani dancers, a Shanghai string band, an X-box competition, chances to play the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ, kids activities, and a drag show (nobody was threatened by those then). So things were pretty crazy.

However, upstairs, in one secluded room, a cellist and pianist presided over a carpet of collapsed listeners, held in a semi-trance for Lord knows how long, by Feldman’s “Patterns in a Chromatic Field.” This 1981 work is the very definition of chill. Over an indeterminate period, the musicians mull over a few pitches, moving in and out of sync with one another, before drifting off to something else. Listeners… well, they just drift off. The floor was bestrewn with Beatniks and flower children submerged in varying degrees of meditation. Of course, being a coffee-drinker and a cynic, there’s only so much of that I could take. But it was amusing while I lasted. A total flipside to the drag show, for sure.

Supposedly, the work spans about 90-minutes, but that isn’t always the case. Anyway, with Feldman, time means nothing in the conventional sense. Later in his career, he often just allowed everything to go untethered. His works would run on for hours, typically at a hush, with very little dynamic variation.

Feldman was associated with the New York School, experimental composers who in the 1950s fell under the influence of John Cage and incorporated elements of indeterminacy or “chance music” into their compositions. This led to the development of notational innovations in his scores. He often employed grids, specifying certain guidelines, but often leaving a lot of the decision-making to the performers or, in some instances, truly, chance. In this way, he was able better to convey his ideal of a slowly-evolving music, with free and floating rhythms, hushed dynamics, glacial pacing, softly unfocused shadings, and recurring, asymmetric patterns.

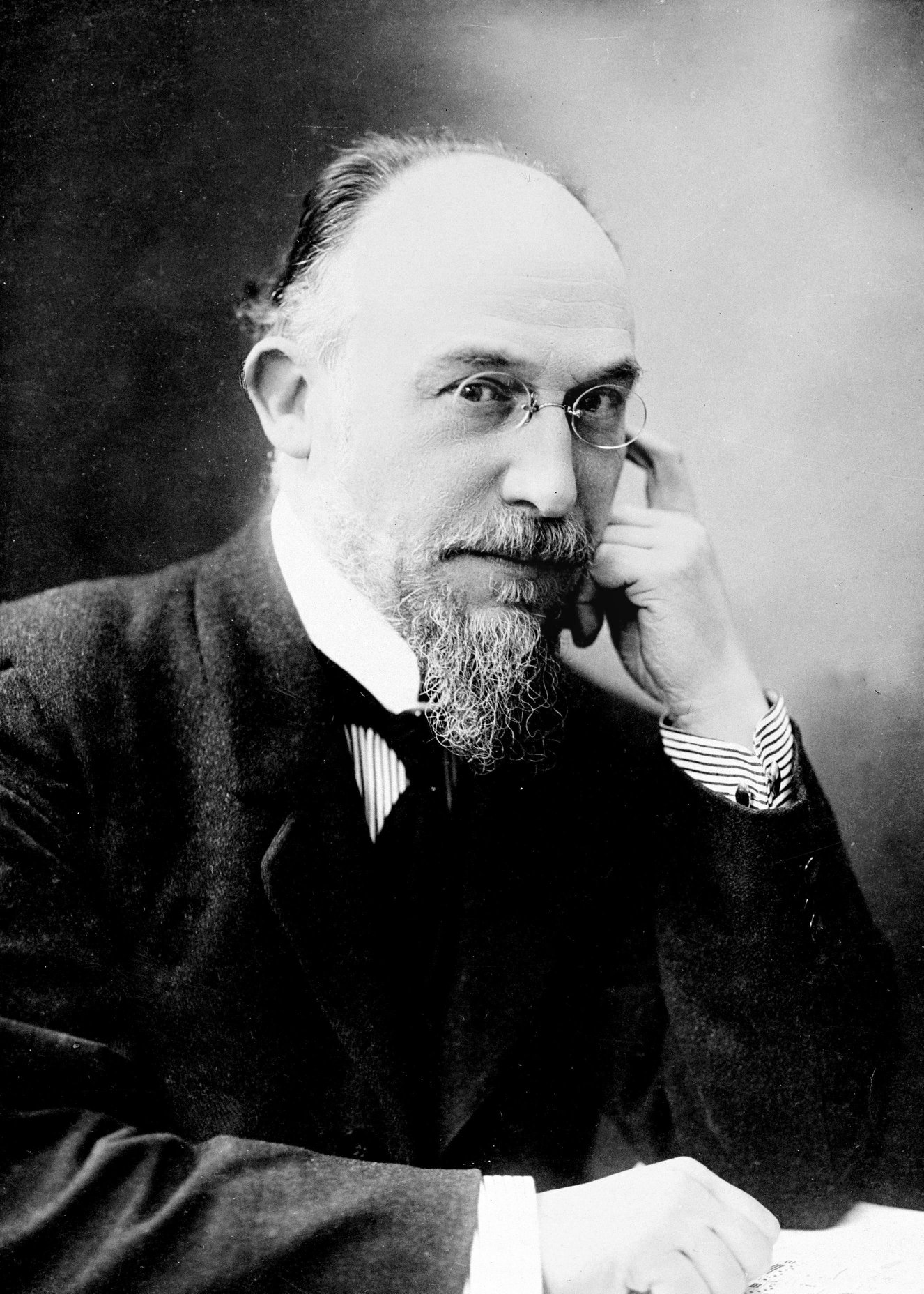

So as you can imagine, it was with great pleasure, and some relief, that I discovered Feldman’s “Rothko Chapel.” “Rothko Chapel” is Morton Feldman for people who think they don’t like Morton Feldman. At 24 minutes, it’s more manageable, certainly more digestible, than many of his other pieces. Furthermore, it is quite beautiful – stark, delicate, and tonal. It was conceived to accompany an exhibition of Rothko’s canvases, in the Houston chapel that bears the painter’s name, a place for contemplation for men and women of all faiths, or none.

Feldman, who was friends with Rothko, organizes his tribute into four sections. “I envisioned an immobile procession not unlike the friezes on Greek temples,” he said. He wrote the soprano melody on the day of Stravinsky’s funeral.

In addition, Feldman specifies in his notes that he was influenced by Hebrew cantillation. Like a lot of his other music, it can be enjoyed as a purely ambient experience. You can listen intently, or just let it wash over you.

On the 100th anniversary of his birth, Feldman’s music continues to quietly, slowly evolve.