Legend has it that, on this date 200 years ago, at the end of a concert at the Kleiner Redoutensaal of the Hofburg palace in Vienna, Beethoven spontaneously rose from the audience to plant a kiss on the brow of an 11-year-old Franz Liszt. The young pianist had just fulfilled an impromptu request from the composer for an improvisation on one of his themes.

Unfortunately, according to Liszt, it never happened. Or rather it did, in a sense, just not on this occasion.

It was actually a few days earlier, at Beethoven’s home, that Liszt received the “Weihekuss” – the “kiss of consecration” – after playing a movement from one of Beethoven’s concertos. Liszt would always remember it as a sort of artistic christening.

He recalled it 52 years later, in 1875, when he was in his sixties, to one of his pupils, Ilka Horowitz-Barnay. The following translation is from Paul Nettl’s “Beethoven Encyclopedia.”

“I was about eleven years of age when my venerated teacher Czerny took me to Beethoven. He had told the latter about me a long time before, and had begged him to listen to me play some time. Yet Beethoven had such a repugnance to infant prodigies that he had always violently objected to receiving me. Finally, however, he allowed himself to be persuaded by the indefatigable Czerny, and in the end cried impatiently, ‘In God’s name, then, bring me the young Turk!’ It was ten o’clock in the morning when we entered the two small rooms in the Schwarzspanierhaus which Beethoven occupied; I somewhat shyly, Czerny amiably encouraging me. Beethoven was working at a long, narrow table by the window. He looked gloomily at us for a time, said a few brief words to Czerny and remained silent when my kind teacher beckoned me to the piano. I first played a short piece by Ries. When I had finished Beethoven asked me whether I could play a Bach fugue. I chose the C minor Fugue from the Well-Tempered Clavier. ‘And could you also transpose the Fugue at once into another key?’ Beethoven asked me.

“Fortunately I was able to do so. After my closing chord I glanced up. The great Master’s darkly glowing gaze lay piercingly upon me. Yet suddenly a gentle smile passed over the gloomy features, and Beethoven came quite close to me, stooped down, put his hand on my head, and stroked my hair several times. ‘A devil of a fellow,’ he whispered, ‘a regular young Turk!’ Suddenly I felt quite brave. ‘May I play something of yours now?’ I boldly asked. Beethoven smiled and nodded. I played the first movement of the C major Concerto. When I had concluded Beethoven caught hold of me with both hands, kissed me on the forehead and said gently. ‘Go! You are one of the fortunate ones! For you will give joy and happiness to many other people! There is nothing better or finer!’”

Liszt told the preceding in a tone of deepest emotion, with tears in his eyes, and a warm note of happiness sounded in the simple tale. For a brief space he was silent and then said, “This event in my life has remained my greatest pride – the palladium of my whole career as an artist. I tell it but very seldom and – only to good friends!”

Beethoven’s conversation book verifies the encounter. What the recollection doesn’t take into account is that by then the composer would have been completely deaf. But he could still feel the vibrations of the piano.

One way or another, I venture to guess, Liszt didn’t wash that smacker off his forehead for quite some time.

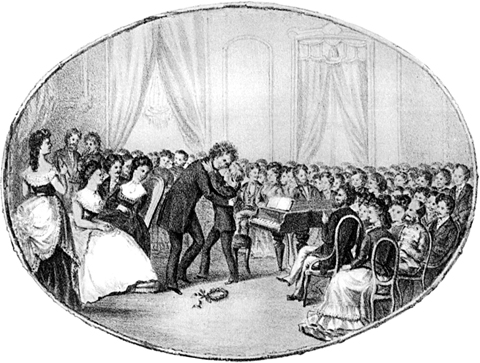

IMAGE: 1873 lithograph to mark the 50th anniversary of Beethoven’s Weihekuss

Leave a Reply