It’s rare to encounter a soloist standing before an orchestra with an instrument as cumbersome in appearance as the tuba; but that is the precisely what happened this weekend, when principal tubist Carol Jantsch took the stage of Marian Anderson Hall at the Kimmel Center of the Performing Arts to join the Philadelphia Orchestra for three performances of John Williams’ Tuba Concerto. And so as not to keep you in suspense, Friday afternoon’s concert, which I took in from the center of Row C in the Orchestra Tier (on the ground floor toward the back of the hall, but out from under the balcony) was superior in every way.

The tuba is an outlandish instrument that comes with a lot of baggage, from polka and marching bands to Tubby the Tuba and Jabba the Hutt. It looks heavy, and it can sound heavy. But the instrument is actually nimbler than one might think, especially in the hands of John Williams and his soloist. The composer, who professed to play the tuba “a little,” describes it as “agile” and compares it to “a huge cornet.” It certainly is lither than any outsider would ever expect.

I don’t know the specifications of Jantsch’s instrument, but a concert tuba can weigh from ten to twenty pounds. There is no chin-rest, strap, or pin to rest it on. You hold the thing and you play it, in this case for 18 minutes. It’s not only an impressive display of dexterity but also stamina. Furthermore, in the grand 19th century tradition, Jantsch lent her own embellishments to the work’s first movement cadenza, working in sly references to Williams’ “Imperial March” and “Jurassic Park.” Not interpolations I would want on a recording, necessarily (it was not Williams’ plan to include these in the concerto), but fun in the moment.

Cumulatively, Jantsch stunned with lung power, breath control, color, and finger work. I sensed many in the audience had no idea what to expect, but they sat in rapt, riveted silence throughout. The music and performance made an electrifying impact, as well they should have.

As if that weren’t enough, Jantsch demonstrated she had plenty in reserve, when, after being called back a couple of times to acknowledge the hoots and applause, she strolled over to join musicians at a keyboard and drum kit stage left, for a cover of “Beastly” by the American funk/soul band Vulfpec, which if anything was more rigorous and virtuosic than the concerto!

She was not gasping afterwards and she never broke a sweat. Unbelievable musician, on the unlikeliest of instruments. But that’s how one gets to be a principal player in the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Williams’ concerto is one of his most immediately accessible and an ideal bridge for fans of his film music. Moreover, the work itself is of very high quality, expertly orchestrated, with the tuba playing with or against various sections or solo players, like a kind of aural kaleidoscope, yet never obscured. The concerto shows off a player’s command of lithe finger work and leather lungs. And it never flags for 18 minutes. (Its three movements are played attacca).

Ralph Vaughan Williams’ is the Tuba Concerto most classical music people are likely to know, but for as much as I love RVW, this one, frankly, surpasses it. Perhaps a less contentious statement would be that if you want to make the short list of most effective tuba concertos, you’ve got a leg-up if your name happens to include “Williams.”

Conductor Dalia Stasevska was midway through her final series of concerts on a multi-week visit to Philadelphia, and quite a visit it’s been. Only days ago, she led the orchestra in a one-off performance of Dvořák’s Cello Concerto – with Yo-Yo Ma, no less. I was not present for that concert, but I was there last Friday for the program of John Adams’ “Short Ride in a Fast Machine,” Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto (with Augustin Hadelich), and Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 (with soprano Joélle Harvey). That concert was up to the Philadelphia Orchestra’s usual fine standards, but I did not find it exceptional. (A couple of other online reviewers were more impressed, though I’m not sure on what day they attended.) For this one, however, Stasevska pitched a perfect game.

The program opened with the Symphony No. 2 by Julius Eastman, a talented and sensitive musician, who attended Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music (Mieczyslaw Horszowski was among his teachers) before pursuing experimental music in Buffalo at the invitation of Lukas Foss. There he worked alongside leading avant-gardists Morton Feldman and Pauline Oliveros. But as a Black man and a homosexual, he faced a lot of impediments, both professional and personal. And he didn’t always address them in the healthiest ways. Among other things, he struggled with substance abuse. For a time, he was homeless. The titles of several of his works include slurs that, if anything, stir even greater outrage now than they did then, so that even to name them would be to risk virulent backlash and an almost-certain ban from Facebook. He was angry and he wanted to shock audiences awake. He had his share of angst, and who can blame him?

Many of his works include experimental touches. His output embraces the disparate influences of aleatory, minimalism, jazz, and popular music (even disco!). None of these are reflected in his symphony.

The Symphony No. 2 was the product of a dying love affair. The composer wrote it at white heat and handed it off to the man he loved. It is a painful, confessional work, introverted and bleak, but also heartfelt and absorbing. It does not outstay its welcome. Most importantly, it reflects the composer’s humanity, which is one of the highest services of music. It doesn’t matter who you are, or what color you are, or who you love, if you have the tools to express yourself articulately in music you can put yourself out there and connect with receptive listeners of all backgrounds. Eastman, at least in this work, does so very well. It’s probable he didn’t actually intend it for public performance. But as a spontaneous outpouring of grief, vulnerability, and tenderness, it is raw and communicative.

Stasevska has been an advocate for the work, and before the performance, she addressed the audience, articulately, informatively, and persuasively, about Eastman and his music. The manuscript of the symphony was rediscovered in a trunk of its dedicatee, the composer’s former lover. It was not in any sense complete, but rather more of a sketch, in 2018 filled-out into a performance edition by Luciano Chessa. How much is Eastman and how much is Chessa, I do not know. A detail that had me raise my eyebrows was an indication in the program that the duration of the piece in performance could be anywhere from 12 to 24 minutes. Not having seen score, I can only guess at the reasons.

I can say that, in Stasevska’s performance, it did not outstay its welcome. I did not check the time at her downbeat, but a recording she made of the work clocks in at around 14 minutes. The music is scored to emphasize lower instruments, employing three bass clarinets, three contrabass clarinets, three bassoons, three contrabassoons, three trombones, and three tubas. A melody suggestive of romantic loss and resultant grief opens onto a desolate soundscape. Instruments drone, but the orchestration is varied and full of interest. The strings wander, but with intensity of purpose, and the orchestra roils. In the original score, Stasevska says, Eastman marked one of the passages “Like Wagner.” Was Eastman recalling “Tristan und Isolde”? Or searching for catharsis in tragedy and grandeur? Whatever his intent, the work is as poignant as it is sonically expansive.

Eastman died in 1990 at the age of 49. His cause of death was given as cardiac arrest, possibly due to complications from HIV/AIDS. It’s said that he was on the verge of starvation. The concert’s programming, perhaps unwittingly, led me to reflect on Eastman’s struggle in comparison with the success of John Williams, his near-contemporary, wildly successful and still active, even as he is about to turn 94.

After a knock-out first half – for many in the hall, I’m sure, full of worthwhile surprises – I felt a bit going into the second half of the concert like a baseball fan entering the ninth inning of a no-hitter. Will the magic hold, or will the charm be broken? I’m not sure if it made me more concerned that the music was Felix Mendelssohn’s beloved “Italian” Symphony, which every classical music enthusiast knows so intimately. A mediocre performance, it would not go unnoticed.

But I needn’t have worried. Musicians of a major orchestra can likely play this one in their sleep. And hey, come on, this is THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA. Needless to say, the musicians played it like it was in their blood. With Stasevska at the helm, the first movement was chipper, at a pace that was on the edge, but didn’t push too hard. (All too often, interpreters mistake rushing somehow for being more upbeat and exciting. It is not always!) It might be Italy, but at the time Mendelssohn visited the Maserati hadn’t been invented yet. It was a pleasure to see the conductor smiling as she oversaw an orchestra playing with such vigor and precision.

The second movement is said to have been inspired by a religious procession the composer witnessed in Naples, but I have never heard anyone take it at a convincingly solemn pace. Thank God for that! I’m not sure Mendelssohn even intended it to be played so. Mendelssohn is the master of flow, and his pilgrims and holy men had just enough espresso to keep it moving at a walking pace, no lollygagging.

“Flowing” even better describes the third movement’s pleasing zephyrs and bird songs. The horn interludes always put me in mind of Mendelssohn’s music for “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” If I were to characterize the symphony from the perspective of this movement alone, I would have no hesitation in calling it his “Pastoral” Symphony.

Except then comes the manic saltarello of the fourth movement, which propels the music relentlessly to the double-bar. By this point, the musicians were playing almost as if they were in a trance, the concentration was so intense. The music glided, fleet, nimble, and cleanly. It was some fancy footwork!

Even before the audience erupted into applause, I found myself marveling anew at what an underrated master Mendelssohn was. He deserves so much better than the enduring slight of a child prodigy who allegedly never fulfilled his promise. Any composer would be elated to have Mendelssohn’s success rate. There aren’t a lot who have so many works in the active repertoire. Will his name pack a house like Mozart’s? That’s not my concern. His best music always speaks to me, and I for one welcome the enchantment of his Romantic creations, which are full of atmosphere and feeling, sometimes touched with gentle melancholy but always without angst.

I am self-aware enough to recognize that any number of internal and external factors can influence my perceptions of a given performance – traffic, weather, the parking garage, an ill-timed email, my blood sugar level, how I slept, whatever else is going on in my life. The list is a lengthy one. I am a delicate instrument! But when the stars align, I have a pretty good ear, or at any rate an experienced one, and if I can keep my brain and my stomach silent, I can give a fair assessment of what I heard.

With that in mind, this concert had a lot stacked against it, as it was only on Friday morning that a glance at the calendar reminded me that I had a 2 p.m. performance. And I still had to get the last of my radio shows in for the weekend! This I produced in near-record time. (I wish I had had more.) Still, it was nearly 12:30 by the time I was able to shave and shower, including a hair wash, probably TMI. Then I had to refresh the bird feeders and hit the road.

Since there was no time for anything else, it meant the old coffee and banana lunch, consumed behind the wheel on I-95. Thankfully, and unusually, the highway was blissfully clear of stopped traffic. I don’t know how I did it, but I managed to make the leap from Princeton to Philadelphia and was seated in the hall well before the start of the concert. Furthermore, I was able to stay focused and attentive throughout. An MLK Weekend miracle!

Even with all that, nothing could dampen my appreciation of this truly fine event. Bravi to Carol Jantsch, Dalia Stasevska, Julius Eastman, John Williams, Felix Mendelssohn, and the Philadelphia Orchestra!

——–

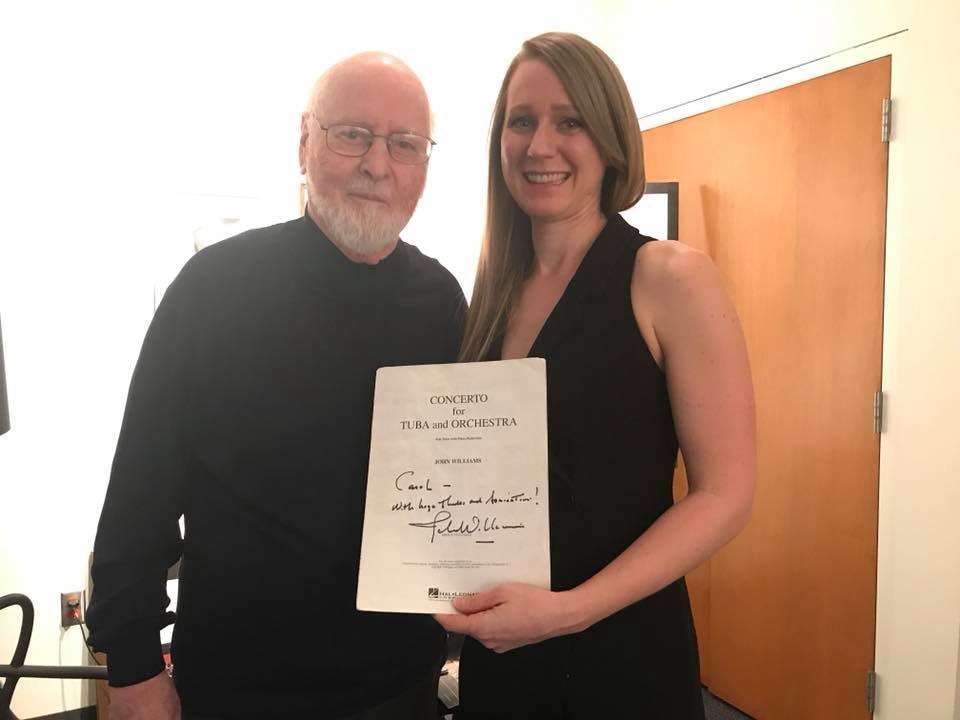

Photo from Carol Jantsch’s Facebook page, taken after a 2018 performance of Williams’ Tuba Concerto, with the composer in attendance

Salterello Vivace to the Philadelphia Orchestra for John Williams’ Tuba Concerto

by

9 responses

Comments

9 responses to “Salterello Vivace to the Philadelphia Orchestra for John Williams’ Tuba Concerto”

-

Great review and synopsis. The photo is from Box 67, tier 1, April 2018, after she first played the Tuba Concerto.

Actually, she does have a support for the tuba, difficult for you to see from the Orchestra Tier. By the way, if you are sitting in the “orchestra level” the first three to four rows in the Orchestra Tier are excellent. Frankly better than the first and second tiers for equivalent seating positions. The third also has exceptional sound quality – for almost the entire Third Tier.

Both Thursday night for the shorter concert and Saturday, the audience broke into applause at the end of each movement of the Italian Symphony. Thursday I can accept the actions as almost everyone is coming to see the orchestra for the first time for Orchestra After 5.

Jack Grimm, the second trombone, was a unique find to play the encore keyboards. Charlie Rosmarin is percussion associate principal; not unexpected for him to play the drum set.

Carol has a cover band called Tubular, which features / featured tubas, euphonium, and drums playing very contemporary music.Media: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10226571639112269&set=p.10226571639112269&type=3

-

Kenneth Hutchins All very informative, Ken, thanks. And LOVE the photo. I saw Williams there a number of times over the past decade or more, but for some reason, I did not attend the 2018 concert. It’s insane that I didn’t, but I must have had a conflict. That had to be it. Otherwise, I’d crawl across glass to hear the Tuba Concerto.

I did NOT see the tuba support on Friday, even though I had a superb view of the stage. I was either too wrapped up in the music, or my eyes aren’t what they used to be. Probably both.

I tried one of those Orchestra After 5 concerts a few months ago, when they did Richard Strauss’ “An Alpine Symphony” and I had a conflict for the regular subscription concerts on the weekend, but I couldn’t deal with the conductor PhanaVision, which I found distracting to the point of taking me out of the music. Good for them for finding ways to bring new people into the hall, but in the future, I’ll be sticking to the regular weekend concerts!

Yannick’s disembodied voice thundering through the hall now between every piece is quite bad enough. Love Yannick as much as the next guy, but hate the P.A. overkill.

-

Classic Ross Amico I’ve heard lots of negative feedback regarding Yannick’s recorded announcements.

In the photo I added Carol is wearing a black belt – in the center is the holder that is used to steady the tuba. When she was part of Higdon’s Low Brass Concerto performances, she discussed the belt – rather discreet. Thursday, I was in the orchestra box just off the stage where the encore took place. When she came out for the concerto, I could see her place the tuba in the holder.

-

Kenneth Hutchins On Friday, the person in front of me was drinking an iced coffee or something. I’d never seen that at a Kimmel concert before. I should have asked her if she’d like a tuba holder for her drink.

-

Classic Ross Amico Unfortunately, some food and many drinks are being allowed into the Hall for orchestra performances beyond the movies with live orchestra. And sometimes with the movies, popcorn is allowed as well. Shaken those cups with ice, munching on contraband popcorn or chips will challenge cell phone and alarm interruptions.

-

-

-

The premise behind Eastman’s Second Symphony reminds me of Billy Strayhorn writing “Lush Life” , composed when Strayhorn was about 18 or so, after a failed romance, a black and gay man, but in the 1930s.

-

Kenneth Hutchins A bummed-out break-up is a bummed-out break-up, no matter who you love. When I think “Lush Life,” I think Johnny Hartman and John Coltrane. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sgbLtG8PBv4

-

-

For the Eastman, three sets of timpani were employed. Since the stage was set without using risers, you may have missed seeing three sets, especially as the program only listed timpani, unlike the trio of instruments for much of the woodwinds.Media: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10226571760675308&set=p.10226571760675308&type=3

-

Kenneth Hutchins Stasevska mentioned the three sets of timpani. I forgot. You could certainly hear them.

-

Tag Cloud

Aaron Copland (92) Beethoven (94) Composer (114) Conductor (84) Film Music (106) Film Score (143) Film Scores (255) Halloween (94) John Williams (179) KWAX (227) Leonard Bernstein (98) Marlboro Music Festival (125) Movie Music (121) Mozart (84) Opera (194) Picture Perfect (174) Princeton Symphony Orchestra (102) Radio (86) Ross Amico (244) Roy's Tie-Dye Sci-Fi Corner (290) The Classical Network (101) The Lost Chord (268) Vaughan Williams (97) WPRB (396) WWFM (881)

Leave a Reply